The “Afterburn Effect” & the Commercialization of Exercise Science

A deep dive on an old trend and how it was misused for financial gain.

12 min read

By: Dylan Dacosta

Things can exist, while also being essentially useless. This right is here is a story about that intersection. In a larger sense, too much of the fitness industry, or my new favourite term, the wellness-industrial-complex, is built on that intersection.

We the consumers, are always looking for that new edge that will help us cruise towards our ambitious goals. We want that new thing that will not only put our results into turbo mode, but will also explain all of our past “failures”.

Whenever that new thing comes around, it starts selling like hotcakes. Or like wheat free, dairy free & soy free hotcakes to be more on brand in this context.

With all this in mind, today we’re going to be talking about the afterburn effect. If you’ve been involved in the fitness and health space for some time, I’m sure you’ve heard of this concept. If you have heard of it, I’m also willing to bet it was sold to you as a revolutionary idea. As someone who was a trainer during it’s height, I for sure sold it to potential clients. For this, I ask for forgiveness — I knew not what I was doing.

If you don’t know or understandably don’t remember it in detail, it’s essentially the marketing term for EPOC, which stands for excess post-exercise oxygen consumption. This refers to an increased rate of oxygen uptake following a bout of exercise that would lead to your body being in an increased state of energy expenditure following that session.

Now, if you’ve heard about this, it was probably communicated to you in a manner that promised it’s ability to transform your body in a the easiest way possible.

Something like this:

“This new way of training will help your body stay in fat burning mode for TWO or even THREE days after your workout!”

The problem with this, of course, is that while such an effect does exist, it also didn’t deliver in the way so many influencers and marketers at the time promised.

The Rise of the Afterburn

I remember this rise around the 2010’s, although it may have been around before then. The fitness industry does have a tendency to recycle fads in a similar fashion to how the fashion industry does. So with this in mind, I’m going to start around this time and accept that I might be missing some highly relatable components that folks older than me might remember vividly.

When I was 16, I was deeply struggling with my body image. This struggle had been lifelong and still carries remnants with me today, but this was a period where I had gained a lot of weight back that I lost when I was 13 and I was in a deeply vulnerable place. So I went to where any confused young boy would go: Youtube.

This was the era where fitness hacks were shameless. There was no industry of evidence based folks dunking on the worst of the grifters yet. This period was the virtual snakeoil salesman’s paradise. And I was on the interweb looking to marinate my brain in that lovely oil.

Cue in, Mike Chang and the company he worked for: Sixpackshortcuts.com — now called sixpackabs.com. This was one of the biggest fitness youtube channels at the time, mostly catered to young men in pursuit of attaining the socially worshipped six pack. This guy’s whole schtick was oriented around the afterburn effect.

Videos like the one above were incredibly common. I couldn’t find many of his old videos now because he’s no longer affiliated with this company and they changed their name along with tempering the over-the-top promises. Although, their website is still full of easy weight loss solutions seemingly targeted at the same male audience.

In short, these videos went through the same, tried and true marketing tactic.

“Have you tried everything?”

“Are you tired of not seeing results?”

“Do YOU want to finally achieve that dream body in the easiest way possible?”

You know the drill.

Then a usually shirtless Mike, would sell you on how targeting the afterburn effect was the way to achieve a body like his. To his credit, he was incredibly charismatic, likeable and had a body that met social ideals.

I fell for this hook, line and sinker. So too, did many other folks just looking for help. Compared to youtube numbers now a days, two million views may seem like nothing, but back then, it was pretty remarkable.

What ensued for me was do these “afterburn” workouts that I truly believed in. Hilariously, I was doing them with a towel. It was a strange 5–10 minute circuit where I was doing rows, squats, lunges and overhead presses while just yanking on a towel to feel some tension. In hindsight, these workouts were incredibly low in stimulus, but placebo is one hell of a drug. I started doing them and combined it with essentially eating nothing. To my shock, I lost some weight — incredible right? If I had some ability to critically think and didn’t just fall for the handsome, muscular man’s schtick, I would have realized that movement of any kind is great and that starving myself would obviously lead to short term weight loss while also being incredibly unhealthy. Instead of that analysis, I, like so many other folks navigating the fitness industry thought I struck magic in a bottle. Or I guess, In a towel? Regardless, I was sold. This stuff was magic to my young mind.

Fast forward and this concept still hadn’t faded by the time I became certified personal trainer a few years later right out of highschool. At this point, it was a commonplace sales tool in gyms. At my time working at multiple big chain fitness gyms, the mention of the afterburn effect or even using the term EPOC was a part of the sales script. I think this was largely about making potential clients feel like they needed us because we had the secret tools to their success, when in reality, hiring a trainer or coach should be about getting the support and guidance you need to reach your goals in a safe and effective manner. Not to gain access to some sort of “Michael’s Secret Stuff” potion or routine. Unfortunately, the latter will just always be more effective of a sales tool. At least in the short term.

The Commodification of Science.

While the sixpackshortcuts platform I mentioned before did have an alleged system built around the afterburn effect, I think the peak of this systemization comes from gyms like orangetheory fitness. Orangetheory Fitness is an international fitness chain that took the afterburn effect rhetoric and built a class based fitness centre around it.

Quite literally it’s called orangetheory because it’s based on the 5 heart rate zones. The goal is for you to spend 12–20 minutes in the orange zone during the workout to “boost your metabolism”, “burn fat” and “burn more calories.”

Taken directly from the home page of the website, the marketing reads as such:

“Backed By Science

Our heart rate monitored, high intensity workout is scientifically designed to keep heart rates in a target zone that spikes metabolism and increases energy. We call it the afterburn”

This is where I have to be harsh. Building an entire brand and business off of this, is to put it bluntly, trash.

This is what I would call the commodification of science. A scientific finding being extrapolated out into a system meant to maximize profits for a private company. This is inherently unscientific. Science is a process. It is not static. Taking a scientific finding and commodifying it into a sell-able system, is essentially pinning the science-butterfly. When you do this, you inherently have to defend this theory at all costs. It’s no longer an idea that is subject to change as new data comes in. It’s now a material business that has a vested interest in this idea being meaningful. If data comes in to disprove it’s efficacy and utility, you can’t be honest — you are cornered into doubling down. I view this as much different than just having a system that you offer to customers because you’ve seen how it can help people. Instead, this is using “science” to persuade customers into buying into your system because “science shows that it works” while also ignoring any science counter to claims.

These are the types of tactics where buzzwords become commonplace. Science jargon becomes buzzwords for marketing. The nuances and applications of the data being referenced is irrelevant if it can’t increase sales. Using the afterburn as an example, I never heard about how much of an effect it had, or if the effect waned over time or even if the effect had any sort of nuance to consider. It simply existed and was going to transform your body. But only if you did these “special workouts” to activate it.

Nuance? In This Economy?

With my diatribe on why I loathe this type of marketing out of the way, let’s dig into some actual science on the topic. Does this effect exist? If so, does it indeed “spike metabolism” and “burn more calories” as many folks and companies have implied over the years?

The short answer is yes.. I guess?? I mean kind of.. but also, not in a meaningful way.

Two small sample studies did compare HIIT and resistance training to see if baseline energy expenditure was increased at two different time points after the workout. One also compared steady state cardio too.

The first one on young men did show a statistically significant increase in 30 minute resting energy expenditure after the resistance training and interval training interventions, when compared to baseline (1).

Pay attention to the words “statistically significant” though. I’ve talked about this before, but this is often used in misleading marketing. Being statistically significant in the statistics world simply means we can reject the null hypothesis. The null hypothesis here would be that there is no difference in resting energy expenditure after one of these sessions and at baseline. The actual effect can be tiny, while still being a significant difference. In this case, 12 hours after lifting, the 30 minute resting energy expenditure in the resistance training was increase by an average of 8 calories and by an average of 12 calories in the interval training group.

If we assume those rates would stay the exact same for 24 hours, that would be an extra ~384 calories burned at rest for the day in the resistance training group and a whopping ~576 calorie increase for the interval group. If this was true, it would be pretty remarkable. But at 21 hours post exercise, the increase wasn’t significant anymore in the interval group (because the standard deviations were quite large at 10 calories) and was still significant in the resistance training group, but down to 7 calories extra over 30 minutes in both groups. So it held moderately well for lifting , but was nearly cut in half for the interval group.

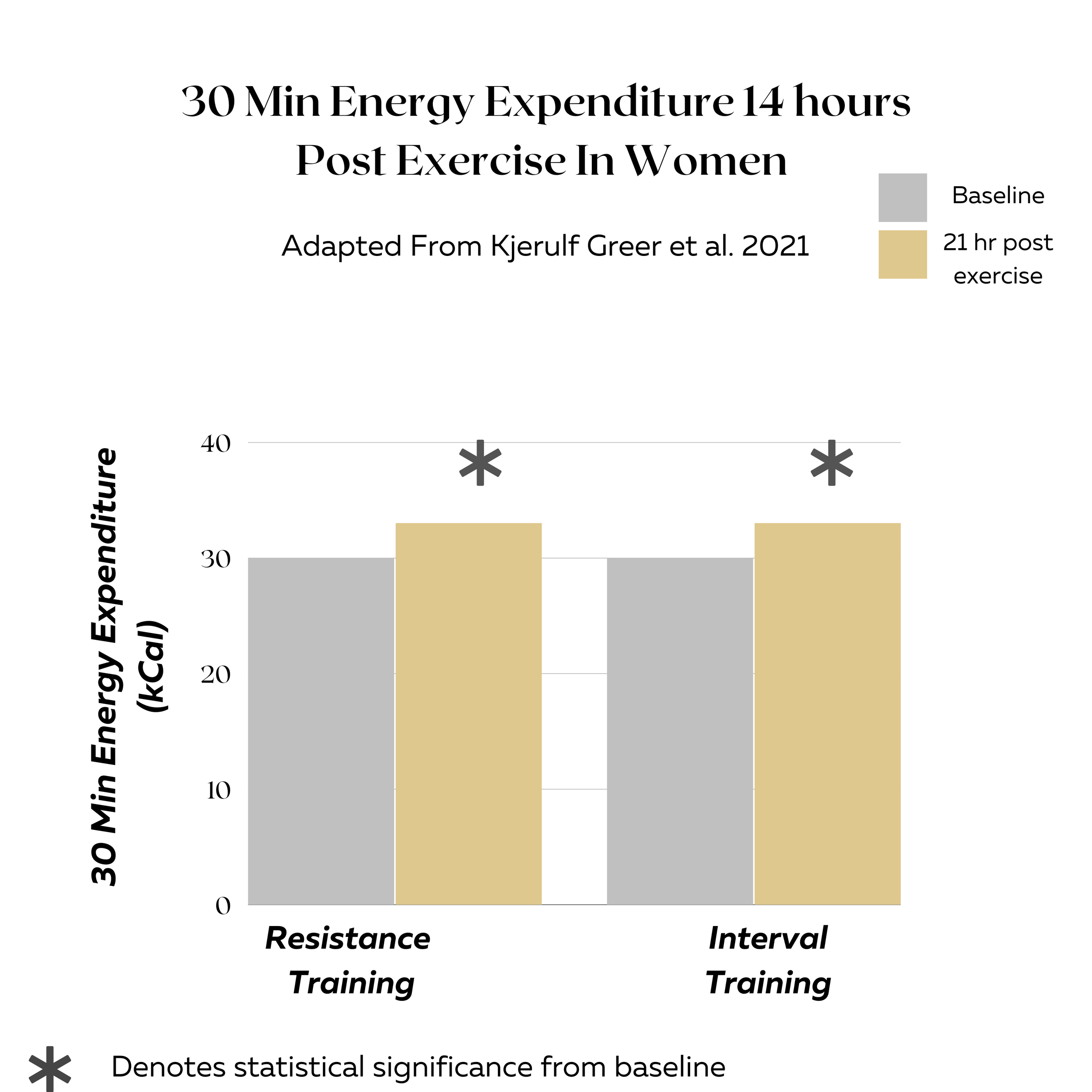

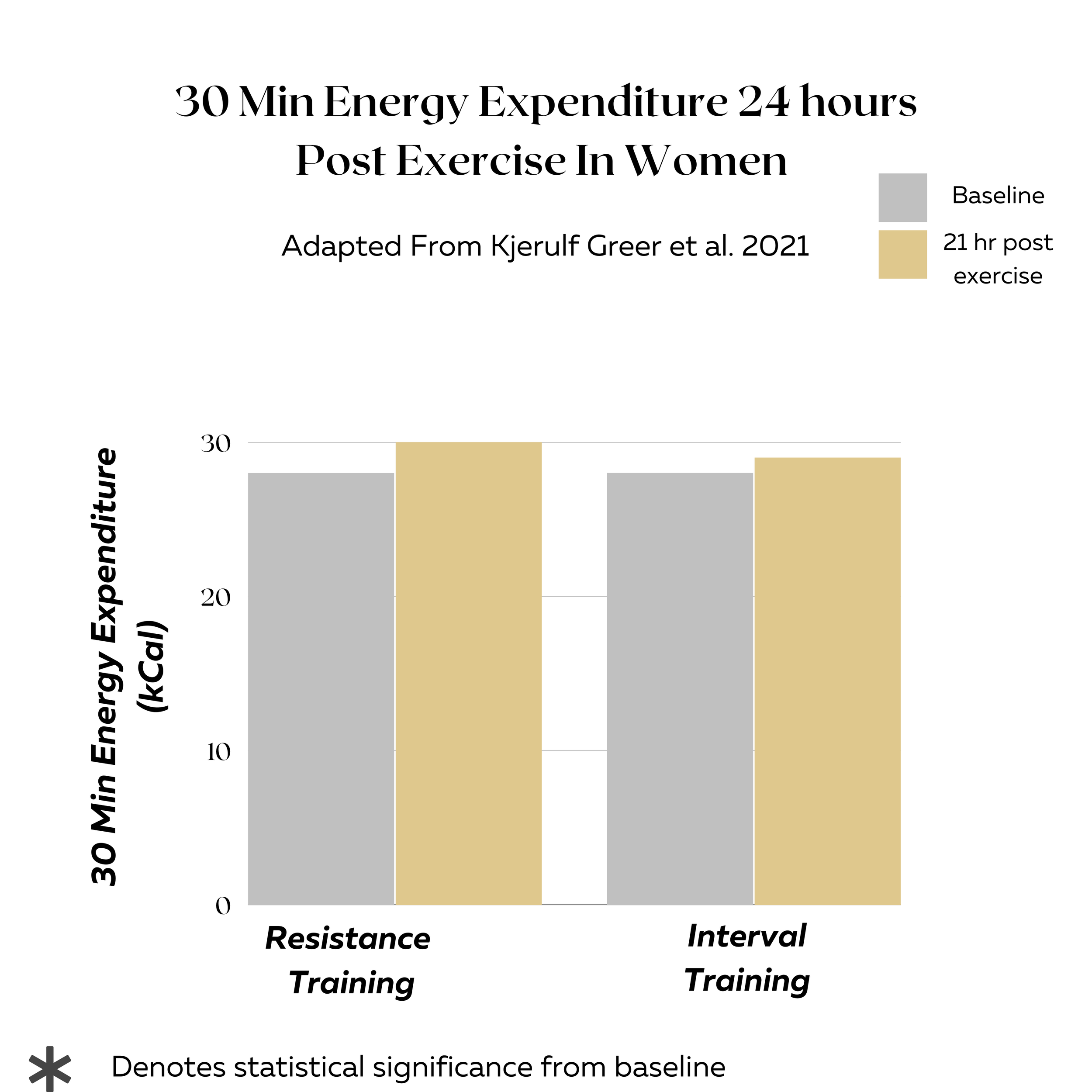

In a separate study (2) on a very small sample size of women, (7 people — exercise science studies of this control tend to be quite small, which is a downside of the literature) the results were even less meaningful. Both groups saw an increase in 30 minute energy expenditure for resistance training and interval training at 14 hours after of 3 calories over 30 minutes. At 21 hours after the exercise sessions, both groups came down a little bit and neither were significant and virtually the same as baseline.

Interestingly in both studies, an “afterburn effect” was also observed in the resistance training groups as well. I mention this because a lot of the HIIT camp folks ascribe their workouts to be unique to giving you this effect. In actuality, resistance training and interval training have been shown to elicit it, even if it is a small effect.

One study from Heden et al. (3) showed that on untrained men, resting energy expenditures were similarly increased for 72 hours when doing one set of 10 exercises versus doing 3 sets of the same 10 exercises. Once again, the effect was around 5% increase for both groups at 72 hours. With their data, the increase would amount to around a 100 calorie increase in 24 hour energy expenditure from this effect.

From https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3071293/ — note that KJ is not calories.

So this effect seems to exist in both interval training and resistance training. Most of the resistance training studies measuring EPOC (afterburn) is also done using resistance training circuits as well (4). This leaves the idea of the orange zone or HIIT being a unique way to send your body into fat burning mode with some egg on it’s face. Lifting also seems to increase your resting energy expenditure after your session.

The next issue is that this is all on resting energy expenditure. Resting energy expenditure is said to account for ~60–70% of your total energy expenditure (5).

Which means this assumes none of the other components of energy expenditure are impacted by exercise. This assumption would be wrong. A compensation effect has been observed from exercise. Some data has shown this effect to average around 28% (6). Meaning if you burned an extra 100 calories from exercise, you’d only have a net increase of 72 calories burned for that day from the additional exercise. It’s also worth mentioning that not everyone will have a 28% compensation. It ranges quite a bit. Reductions in NEAT (non-exercise activity thermogenesis — think of all your movement in the day that isn’t intentional exercise) are likely to be the culprit here.

So while there is an observed afterburn effect from exercise, there is also an observed compensation effect. Which is one of many reasons why exercise alone tends to not be the greatest stand alone method for achieving weight loss. Along with that, the afterburn effect has not observed to be very meaningful in the grand scheme of things and also isn’t unique to special HIIT training.

So.. It’s All a Scam?

No. Not entirely. Exercise is amazing for so many reasons. If you were convinced to doing some sort of hard training to utilize the afterburn effect, you were mislead, but not scammed per se. At the end of the day, you still trained hard and that’s awesome. You may have also met some cool folks at a fitness class and even found an instructor that motivates you or a style of training you enjoy. These are all fantastic. All of this can be true, while at the same time it being true that this effect was more of a marketing tactic than it was some magic bullet for fat loss.

If you loathe that style of training, I hope you realize you don’t need to do it. When it comes to exercise, finding a style you enjoy and can stick to is top priority. If you’re only doing it because some fancy advertising convinced you that you need to, I’m doubtful you’ll stick to it long term. Or that if you do, it would be out of fear of missing out on some ascribed special benefits as opposed to because you enjoy it and are seeing great results from it.

The afterburn effect is just another example of marketing rhetoric masquerading as meaningful scientific findings gone awry. I wanted to write about it because I find it interesting how powerful these tactics are and to also inform you, the reader, of how misleading these tactics can be. There is no shame for falling for it. I’ve fallen for it as well. I’m also not arrogant enough to act like I’m impervious to misleading advertising either. I especially notice it when seeing advertising from fields that I don’t work in. It reminds me of how powerful effective marketing can be — regardless of the promises are relevant or not.

Conclusions

The afterburn effect, or EPOC, does exist.

It’s existence doesn’t mean it matters though. From the data available, the effect likely won’t make a meaningful dent in your overall total daily energy expenditure.

Post exercise increases in resting energy expenditure are also seen from resistance training workouts too. Making the uniqueness ascribed to HIIT style training for the afterburn effect incorrect.

There is also a compensation effect from exercise. Exercise will generally increase total daily energy expenditure, but perhaps not to the degree you’d think.

Exercise is still amazing for so many reasons. Focus on finding a style of workouts you enjoy or in an environment you like being in first. This will be important to help increase adherence, which is much more important than finding the “perfect workout”.

Remember, pretty much everything on the internet is an ad. Even this article is advertising my writing and coaching. Not all advertising is a lie, but it is biased. Be skeptical when consuming fitness content. If something sounds too good to be true, it likely is. The afterburn effect is one example of this.

Cheers,

Coach Dylan 🍻

References:

1. EPOC Comparison Between Isocaloric Bouts of Steady-State Aerobic, Intermittent Aerobic, and Resistance Training

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25675374/

2. EPOC Comparison Between Resistance Training and High-Intensity Interval Training in Aerobically Fit Women

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8439678/

3. One-set resistance training elevates energy expenditure for 72 h similar to three sets

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3071293/

4. Influence of Resistance Training Variables on Excess Postexercise Oxygen Consumption: A Systematic Review

https://www.hindawi.com/journals/isrn/2013/825026/

5. Biology’s response to dieting: the impetus for weight regain

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21677272/

6. Energy compensation and adiposity in humans

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34453886/