How to Build Habits That Last

Your guide to understanding habits and how to change them.

20 min read (4500 words)

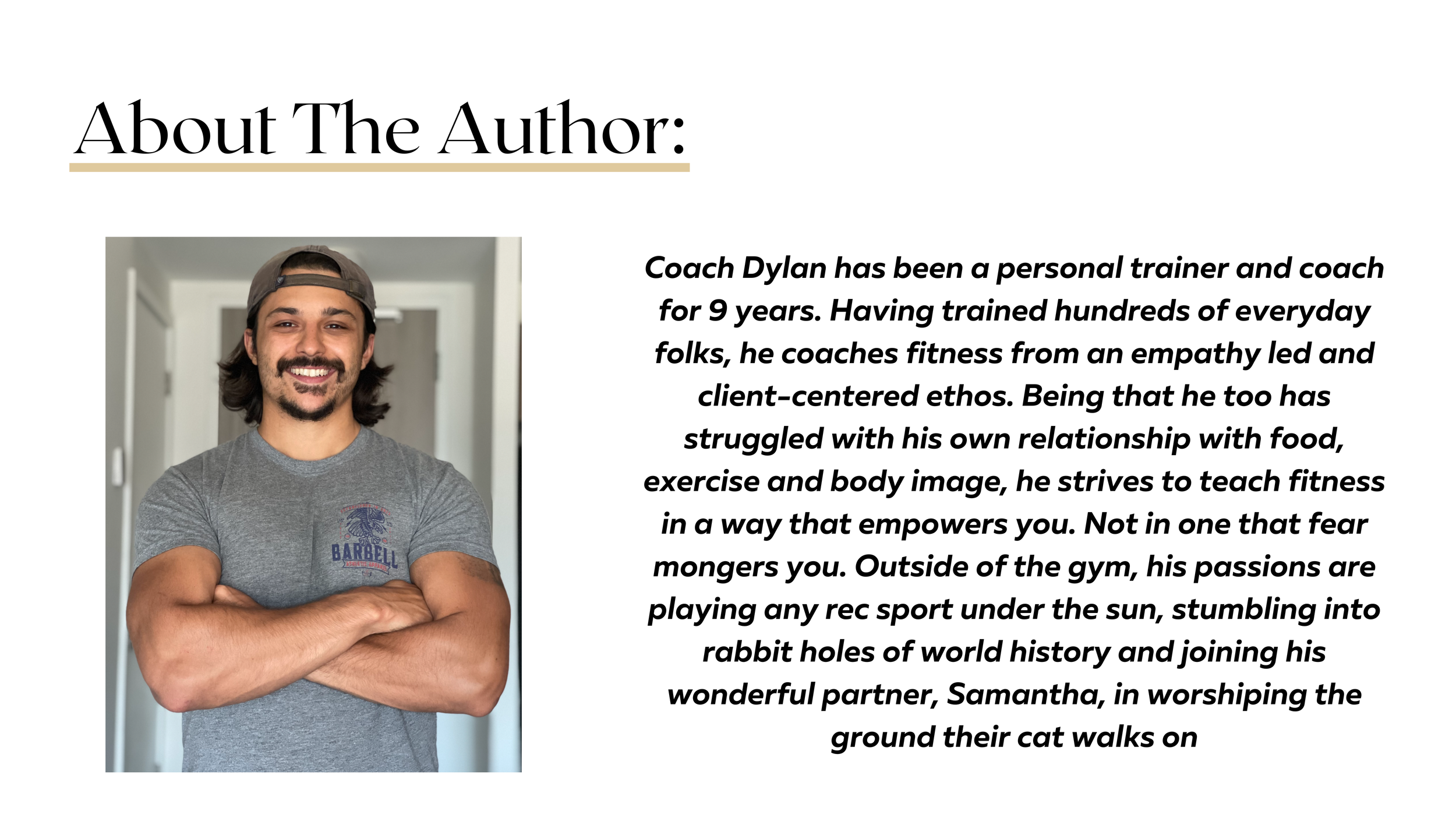

By: Dylan Dacosta

Sparknotes:

-We all have habits. They can work for or against our goals, but your environment (cues) and repetition play a big role in solidifying them over time.

-If you want to develop/break a habit, intention is important in the beginning, but using cues, adding/taking away friction and repetition are the key components to developing habits and their strength.

-To develop habits for long term success on top of some habit forming strategies, tying them into your value driven goals and desire for self determination can help develop a feedback loop that's internally rewarding and may strengthen your habits even more.

-Read below for a deep dive full of helpful tips!

Have you ever driven through a traffic light and thought “wait, was the light green?” I know I have. Countless times.

Almost assuredly, the light was in fact green. This is how powerful and automated a habit can be. This also highlights how much a role repetition plays in the strengthening of a habit. The first time you drove through a traffic light, I’m willing to bet you consciously took in the colour of the light and made a conscious decision in light (pun intended) of what the traffic light showed.

If you’ve driven a lot, this behaviour has likely become so ingrained that you just automatically respond. So much so that the experience of literally not remembering whether that light was green or not is common.

This is the power of your habits at play.

When it comes to your fitness goals, developing and strengthening habits that align with your goals is crucial for your success.

I know what you’re thinking. “I don’t need habits that work for me. I just need to work harder in order to achieve my goals.”

This is what the “self-discipline” narrative that is oh-so-pervasive in the fitness industry has done. Fitness enthusiasts who succeed with their fitness endeavors have gaslit the average person into believing they’re “successful” because they simply work harder than everyone else.

This belief can only exist if we look at the external output of the “work” being done. If we’re measuring how “hard” one works by how much their output is, then sure, the fitness outliers on average probably do work “harder” than the average person.

Except, this erases the role that habits and environment play in this equation.

I’ll skim over the fact that most outliers are understandably going to self-select into the activities they excel (and are outliers) in.

We humans, love being good at shit. And we all have individual responses to certain activities. For example, if you look at the data in any exercise study, you’ll be given the average outcomes. This excludes the individual responses.

Even under any tightly controlled intervention, someone is in the 1st percentile and someone is in the 99th percentile. Even though they both did the exact same, tightly controlled intervention.

One example from a study (1) I covered previously demonstrates this. While the average outcome is shown, so are the individual data points. The highest responder in whole hamstring muscle growth had about 4 times the greater gains the the person who gained the least amount of muscle. They were both untrained and did the exact same program.

Now this was a small sample size so this person probably isn’t an actual outlier, but I’d venture to say they’d probably be more inclined to enjoy strength training more than that person who had 4 times worse gains. As I mentioned, humans love doing things we're good at. Especially when we’re celebrated for it.

I say this, because the folks you see on social media flaunting their remarkable bodies and unfathomable athletic performances are likely outliers, or at least, high percentile responders to fitness. In this case, they may not in fact be working harder than you. But instead, they just picked better parents (sarcasm implied).

Or they may have worked equally as hard as you in the beginning, got exponentially better results, a higher sense of reward and greater sense of community within that activity now.

This sense of reward may have driven their desire and motivation to keep showing up and the more they showed up, the stronger their habits became. Now, even if they are exerting a lot of brute force in the gym, the cognitive effort (willpower, self-discipline, etc.) they need to apply to their fitness-oriented lifestyle is minimal compared to the below-average Joe they left a trail of dust in front of in the prior, sham comparison.

I share that tangent to respond to the idea that “you just need to work harder”. Yes, of course hard work is important. But if you were to follow the outliers, you’d be surprised to see it’s not like they’re just making rigorously hard decisions all day in the face of opposing forces.

They more often than not have a lifetime of habits driving their behaviour toward their goals. In terms of habits, the hard work is in the beginning, but as those habits strengthen, the rigor of the effort needed to maintain them tends to diminish as the habit becomes more automatic.

Case in point: Driving.

The first time you learned to drive, you were probably mentally gassed from trying to remember and stay on top of everything. Now, I bet it’s not uncommon to get in the car and get all the way to a destination without feeling like you were present or cognitively applying any effort at all.

With this in mind, I hope I’ve made a good case in that the “work harder” approach is not ideal in the long run. Working harder in the pursuit of developing goal-conducive habits that will start to work for you, is a much better approach in my opinion.

So let’s get to some practical ways you can apply this towards your fitness goals.

Understanding Habits:

First off, habits and behaviour are not the same thing. They’re related, but not the same. A great definition of a habit from this review paper (2) was:

“a process by which a stimulus automatically generates an impulse towards action, based on learned stimulus-response associations.”

In addition the idea that “They form through repetition of behaviour in a specific context” was also mentioned.

If you’ve ever read popular habit based books such as Atomic Habits, by James Clear or the Power of Habit, by Charles Duhigg, this will be reminiscent of the “cue, action, reward” cycle.

Stimulus can take many forms. It can be visual, auditory, or even derived from a smell. E.g. you smell baked goods and the get the impulse to wander over there and see where all that goodness is coming from.

As the definition up top highlights, an impulse is automatically generated. This is different from an action being automatically generated. The former does allow for deviance from the impulse and some amount of agency. The latter implies essentially no free-will in the matter.

Some stimuli are so strong that no agency enters the equation. E.g. you touch a burning hot stove and your nervous system responds reflexively by pulling your hand off the piping hot surface before your brain could consciously choose to do so. Even the biggest self proclaimed “free thinker” yields their embellished sense of free will in this example. But for less aggressive examples, the amount of cognitive awareness and effort will teeter along a spectrum.

It can be helpful to think of a habit as a process. Not just as an outcome. The process involves the stimulus (cue), the drive to action (impulse) and the outcome. If that outcome does involve the action, it can also yield a reward. This reward can play a powerful role in engraining the habit going forward as well. Hence why some of the most highly rewarding behaviours can become habits faster than less pleasurable ones.

Developing Habits:

If you want to develop habits, decision making and intentions are going to play a big role in the beginning. Especially if you’re trying to change a habit.

If you have a habit you would like to kick, the first place to start is not by saying “I am no longer going to do that anymore.” You’ve done that before. So have I. It’s a shitty strategy for behaviour change.

Instead, identify what the cue is. This is a great place to start. Here is an example (and a common one):

You eat nutritious foods in line with your goals all day. This includes dinner. You’re feeling good about your decisions. Once you sit down on the couch to watch TV, you find yourself mindlessly snacking on foods you wish you weren’t. This happens way more than you’re comfortable with, but you can’t really understand why.

You could make the mistake of just saying “I just need more willpower”. But like… how’s that worked for you in the past? I’d bet that house on the answer “not very well”.

Instead, take some time to identify what the main cue is that is driving that impulse to mindlessly snack while watching TV.

Eating out of boredom is not uncommon. If you’re feeling bored while zoning out on the couch (my favourite activity), that environment may generate the stimulus to look for something to munch on. If you’ve done this countless times, that habit has likely become stronger over time.

Whatever you identify here should now be a key part in your strategy to disrupt this habit.

You can try using this cue to prompt a different behaviour or you can completely disrupt the sequence of events with this habit entirely.

Example of habit:

-You eat dinner, clean up and put the kids to bed.

-You head to the couch and put on something to watch.

-You’re feeling bored and get an urge to see if anything interesting lies in the pantry

-Before you know it, you’re hand-in-bag, mindlessly munching on some popcorn, thinking “how did this happen again?”

Let’s look at some possible strategies to change this habit.

This isn’t a surefire strategy to work, but you’ve at least reduced any exposure to visual cues and the deep breaths might help with breaking the mindless loop you may feel stuck in. A strategy like this is probably best for those who don’t want to change the habit of watching TV.

Additionally, I mentioned you can place snacks in a less convenient place. This is an approach called “adding friction” and it can be incredibly helpful. Sometimes, even just the slightest amount of friction can change behaviour. This was a big part of the public efforts to reduce smoking in plenty of places. At one point, smoking inside was common place - even some healthcare workers were known to smoke inside of hospitals. Now smokers have been relegated to leave where they are and smoke outside if they must. Smoking companies also can’t advertise in the ways the used to. This reduces visual exposure, which in this context would be a cue. Just like the vulnerable, potential smoker could visually reminded to buy that pack of smokes by seeing the onslaught of advertisements with their favourite celebrity smoking, you seeing your favourite snack in your direct line of vision could drive that automatic impulse to get up and grab a handful.

For example, in Canada, tobacco products can only be advertised at adult only venues. If you want to change a habit, following suit here would be wise. If you find yourself mindlessly snacking against your best intentions, add friction to your ability to grab those snacks and removing visual exposures are simple and easy strategies.

If you have a multiple floor home and find yourself snacking mindlessly, ask if you’d still mindlessly grab that snack if it was placed on a different floor than the one you were currently on. Odds are, your odds of mindlessly snacking would reduce.

This example is less likely to stimulate that impulse to head to the pantry since you’ve changed up your activity, but who knows? Being on the couch alone may actually drive that impulse the most.

If that’s the case, switching up your environment might be helpful. This can be as simple as sitting on a different chair or reading in a different room. Play around and see what works for you.

There is also a priming strategy I skimmed over there. Placing your book in a more convenient place than your remote. This is using friction again, but in the opposite manner. Here you’ve reduced the friction of grabbing your book since it’s placed in that convenient spot. If your goal was to read instead of watch TV, having that book in a more convenient and accessible place than your TV remote could make your decision much easier.

In a more aggressive example, I used to unplug my Xbox after every use. So if I wanted to play, I had to plug it back in and couldn’t just press the “on” button. This may seem benign, but countless times, this little bit of friction reduced how much I was gaming. You don’t have to take it that far, but if you want to reduce a habit, add more friction. If you want to add a habit, reduce friction.

This will take effort and can be identified as an action step. An action step is something you may do to make your habit practice run more smoothly. If you got down to the couch, tired after a full day and the remote was right there, but your book was in a different room, you obviously can still grab the book, but the odds are not in your favor. Do yourself a solid and set yourself up for success. Subtle things like this may seem trivial, but in my experience, they do make a difference over time.

To highlight this example, imagine how automatic your drive/commute home from work can feel. Now, imagine how less automatic that commute may feel if you had to make one small detour.

That’s what this example is, a detour.

I’ve seen this work before and it can be surprisingly helpful. Imagine your evening routine in a larger sense. You may feel a bit automated from dinner on if it’s the same series of events, over and over again. With that final event frustratingly resulting in you snacking mindlessly on the couch while watching TV.

The detour can disrupt this and may help with changing up some of your habits.

This is by no means the extensive list of habit changing strategies. This is just to highlight some small changes you can make to disrupting your cues/environment that driving the impulses to the unwanted behaviours you’re engaging in.

Based on some of the literature I read for this article (2) (3) (4), it was to no surprise, that repetition of the desired behaviour is crucial for developing a habit.

There is a positive feedback loop in repetition, too. As in, the more you repeat the behaviour, the stronger that habit becomes.

One study (5) on 96, mixed sex, UK adults (age 21-45) showed that when adopting a new, self chosen, “healthy” habit for 12 weeks on top of something they already did (a cue), the median time it took for the self reported strength of habit to plateau was 66 days with a range of 18-254 days.

Averages tend to accelerate up quite fast (fast learning curve of habit strength) and then tail off. One example showed that simpler/easier habits tend to form quicker. E.g. walking for 10 min after breakfast was easier for developing self reported habit strength than doing 50 sit-ups after morning coffee.

This evidence supports the idea that repetition can help improve habit strength, otherwise known as “automaticity”, in the literature. The more automatic your habits are, the more likely they’ll continue to happen.

This study also addresses the all-too-common “it takes (insert random number) of days to form a habit”. In reality, there really is no specific number of days it takes. Each individual will form habits at a different pace, and each habit will generally be easier or harder to form as well.

Self-monitoring can be valuable in this context. Assessing your compliance of the habit you’re trying to adopt along with assessing how much effort is needed to upkeep that compliance can come in handy.

If a habit is becoming second nature and being done consistently, this could be a good time to focus on a new habit or goal. If you’re still struggling, adding another habit practice could be a recipe for disaster.

Putting It All Together

To wrap this up, I’m going to pull together some other behaviour change topics I’ve discussed before and combine them with habit formation strategies to help with your fitness goals.

I want to intersect three ideas here.

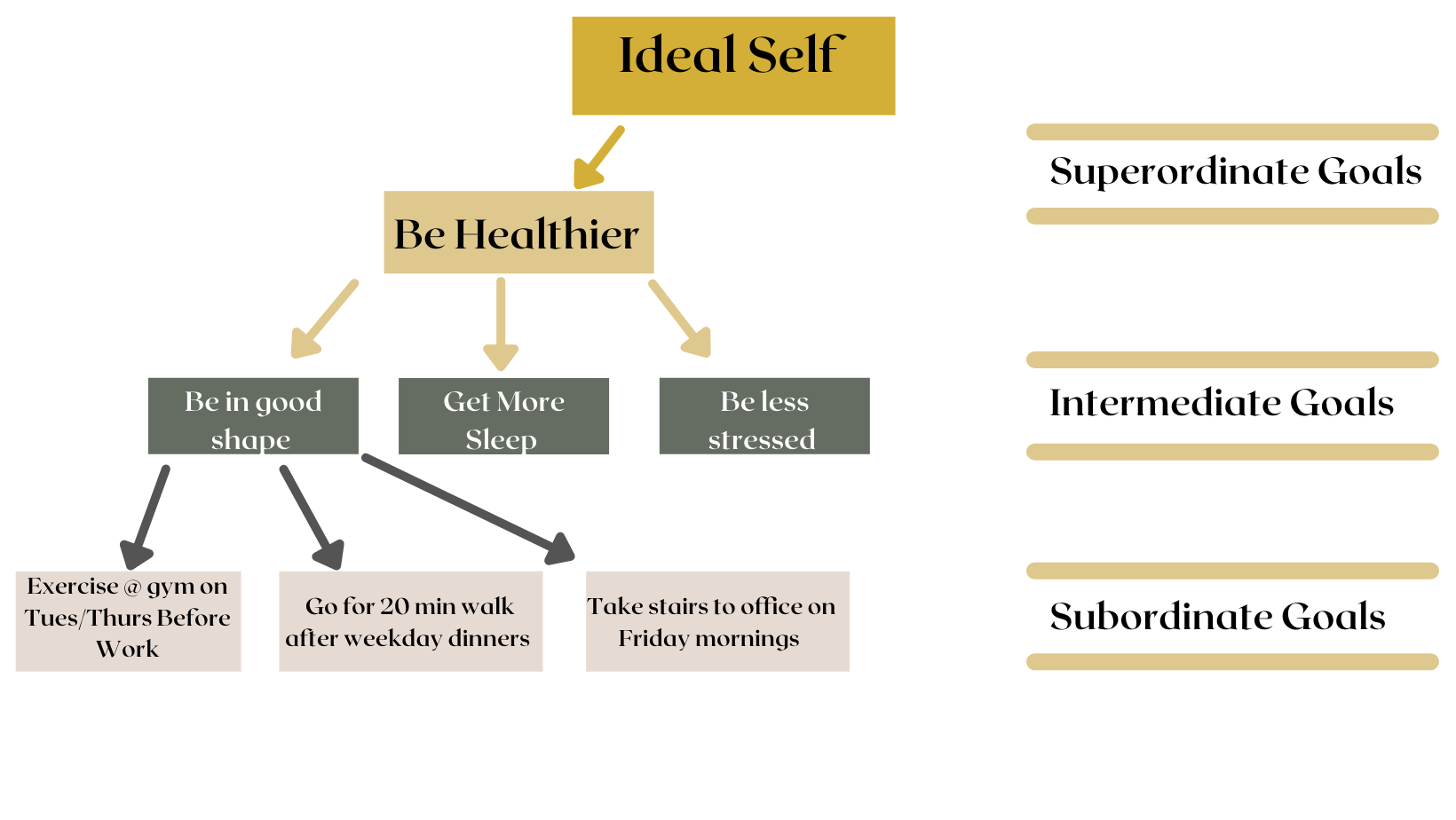

1. Setting up a value-driven, goal hierarchy

2. Using some self determination theory in your decision making

3. Using best practices in forming habits that align with your goals

For the goal hierarchy, read a deep dive here. For the sake of this article, I’ll hit the high notes.

Essentially, you want to establish a goal hierarchy that is governed at the top by broad, identity based goals you have (6). I.e. be healthier. These identity goals should be ones you’ll aspire to indefinitely because they’ll drive you to keep striving toward the best version of yourself (in your opinion).

If you don’t know where to start here, establishing your values is a great place to start. Your values will be key in shaping what your ideal self actually looks like, according to you.

From there, you’ll want more intermediate goals that are more specific and will support the pursuit of your identity based goals. If your broad goal was to be healthier, then the intermediate goal might be to “get in better shape”.

From there you’ll want subordinate goals. These are the highly actionable ones. These are the ones you want to turn into habits. If your intermediate goal was to “get in better shape”, then having an activity based subordinate goal makes the most sense.

This could look like “Workout two times per week on Monday & Thursday before work following X routine at the gym by work.”

In this example, you now have a specific habit you’re trying to adopt. This may take some action steps (sign up for gym, budget time, pack gym clothes etc.), but once those are done, you’ll have the blueprint to start adding reps to that behavior and forming your habit.

Secondly, using self-determination theory can be helpful here as well. Read a more in depth article on the topic here. In SDT, three key psychological needs are the need to feel a sense of autonomy, to feel competent and to feel a sense of relatedness.

I highlight this because in one of the prior studies mentioned (5), subjects chose which habit they wanted to do. This hits the autonomy part. They weren’t just told what to do. Instead, they were given a list of suggestions by professionals and they chose which one they wanted to do. This likely touched on the competence part too. It’s more likely you’ll pick a habit you believe you can do as opposed to one you know you can’t.

Relatedness comes into play if you are sharing this experience with someone else or in your community. Having support from people you feel like “get” and can support you, goes a long way. This can be a little more vague, but in the gym example, finding a gym with a supportive environment or even going with a supportive friend can be quite helpful.

SDT mentions motivation being on a continuum. The idea is to try and develop intrinsic motivation. This is a motivation that is integrated compared to extrinsic. Extrinsic motivation may be tied to some form of reward or avoiding punishment. E.g. you train super hard and cut calories in order to look lean on your beach vacation so that people will (a) tell you how great you look - reward. Or (b) not shame you for how you look - avoid punishment.

I’ve done both of these. I’m not judging anyone for ever having an extrinsic motivation like this either. The point is, it’s hard to uphold behaviour long term solely for extrinsic motivations such as these. It’s also probably not great for your mental health, since ya know, part of your value would be contingent on maintaining a certain body size and having that validated by others. Said out loud, that kind of sucks.

If your motivation was more intrinsic and integrated, you’re going to be set up in a better spot for the long term. Intrinsic motivation comes when you’re doing something because that behaviour is consistent with your goals and values. (7)

In this example, you’d be engaging in exercise because it aligns with your goals and values of being healthier. When you do engage this, you may feel a sense of reward because you’re honouring your values with your actions. In fact, some research has observed intrinsic motivation to correlate positively with the habit of physical activity, with external motivations correlating negatively with the habit of physical activity. (8)

I mention reward because it’s often mentioned as being a key part of habit building. The only issue with establishing a reward, is that it’s common to set up an external reward. If you’ve been trapped in a crash dieting cycle, a cheat day would be an example of an external reward.

If you eat “healthy” all week, you earn the reward of cheating on a friday night, saturday night, or even the whole weekend.

To avoid setting up too many external rewards, having your behaviours line up with your identity based goals can help achieve a sense of intrinsic reward. In this example, the reward is the feeling of living in line with your values. External outcomes can reflect this nicely. E.g. you hit a PR in the gym that took a lot of effort and time to achieve. You achieving that PR is reflective of your training consistency, which ignites a sense of internal reward because that external outcome was evidence of you living in alignment with your values and making progress towards your broader, identity based goals.

This is an example of how you can use internal reward as a feedback loop to keep you training and thus, staying committed to acting in alignment with your values and continually striving towards that ideal version of yourself.

Lastly, now that you’ve established your goals and how you can live in alignment with your values while leveraging strategies that keep you intrinsically motivated and feeling a level of autonomy, competence and relatedness, we can start to use some effective habit strategies to solidify these behaviours down.

Let’s imagine you’re struggling to get to the gym and stay active. In this case, you want to identify what is putting the most friction in the way of you and training.

Sometimes, this is internal. If you just simply can’t train four days a week, but you’re being too headstrong in expecting that you will, you’ve created this friction. You’re setting yourself up to fail and feeling like you’re “failing” is a great way to snowball into abandoning ship. If this resonates, make sure your ambitions aren’t a big piece of friction. In other words, make sure you can actually do what you’re setting out to do (remember competence from SDT?)

Friction may also be that you’re not planning and taking the appropriate action steps to make this goal a reality. Say you can manage training two times a week. Awesome. Find those two times and schedule them like you would an appointment. If it’s just an idea in your mind, it’ll be the first thing to be abandoned when the inevitable chaos of life ensues.

Secondly, streamline the process of what it will take to get that workout in. This means making sure you have your gym clothes/equipment ready, time budgeted and your actual workout plan ready to go. You don’t need to have an elaborate plan either. This is habit building, so I don’t care if your plan is just to get to the gym and walk on the treadmill for 20 minutes. It’s not about having the perfect workout, it’s about solidifying the habit of exercise. You can also find some simple workout programs online and if you need extra help, you can check out what we offer with online coaching. Regardless, this doesn’t have to be complicated.

Lastly, prime your environment to encourage this goal. Having a cue to remind you of this goal can be powerful. This can be as simple as having a reminder in your calendar to get going to the gym. It can also look like having that gym bag ready and visible in a convenient location. That image can remind you of your goal. Say your goal is to go to the gym after work. In that case, keep your gym bag on hand and visible (in your car or on your person) as a visual cue to what your goal is. It’s honestly really easy to forget, get overwhelmed or just straight up bail without any cue. Cues are a powerful component of behaviour change. Use them to your advantage. Just like removing visual cues to snack (i.e. not having a bowl of chips right in front of you) can help, adding in visual cues to encourage a behaviour is another great strategy.

In this example, the cue is the visible gym bag/scheduling reminder etc. the action is going to the gym or wherever you go to train and the reward is feeling like you’re living in alignment with your values since you’ve already established those values and hopefully feel a sense of attachment to them.

This will be hardest in the beginning, but inertia and that sense of reward, strength of habit, perceived competence and autonomy will start to develop and it’ll become easier and easier as time passes. Similar to how habits that you don’t want to engage in (unwanted snacking, checking your phone etc.) get stronger with repetition, the habits you do want to engage in also get stronger the more you do them. If you can find a way to have those habits directly feed into your intrinsic motivations and desire for self determination, you’ll be cooking with gas.

Cheers,

Coach Dylan 🍻

References:

Greater Hamstrings Muscle Hypertrophy but Similar Damage Protection after Training at Long versus Short Muscle Lengths

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7969179/

2. A review and analysis of the use of 'habit' in understanding, predicting and influencing health-related behaviour

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25207647/

3. Making health habitual: the psychology of ‘habit-formation’ and general practice

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3505409/

4. healthy through habit: Interventions for initiating & maintaining health behaviour change

https://behavioralpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/BSP_vol1is1_Wood.pdf

5. How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ejsp.674

6. How Focusing on Superordinate Goals Motivates Broad, Long-Term Goal Pursuit: A Theoretical Perspective

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01879/full

7. Self-determination theory: its application to health behavior and complementarity with motivational interviewing

https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1479-5868-9-18

8. Does intrinsic motivation strengthen physical activity habit? Modeling relationships between self-determination, past behaviour, and habit strength

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22760451/