We All Respond Differently to Training

Even when doing the exact same program, results vary for every individual.

7 min read

By: Dylan Dacosta

Have you ever had a training partner that got annoyingly better results than you? Even though you both trained together and did essentially the same program? If so, you know personally how demoralizing this can be.

I’ve been on both sides of this outcome. I’ve been both the lucky and unlucky spouse in the intimate bond that is a lifting partnership. This seems unfair, and it is. It’s just also to be expected.

Too often, we use outcomes to draw conclusions. Yes, I’m aware of how scientifically illiterate that sounds. What I truly mean is that we use raw outcomes without accounting for unequal variables when we draw conclusions.

The one I’m talking about here is the individual response to training. In a utopian world, the results you get in the gym would be directly proportional to the effort you put in, which would be standardized with your peers.

We don’t live in that world. Instead, we live in one where we all know a beast who barely trains, eats whatever they want and is still more jacked and strong than we are while putting in exponentially more effort than them.

What’s even more infuriating is that the genetic 1%’ers of the world are often assumed to simply work harder than everyone else. While some do, this is not an inherent truth.

I myself am someone who responds quite well to training in terms of getting strong and building muscle. I can also admit I’ve trained plenty of folks who train significantly harder than I have and just don’t respond to their training as well as I do.

I also know that one factor that played a role in my becoming a coach was that I responded well to my training and thrived in the gym environment as a result. Put simply, it’s easier to get hooked doing something you’re naturally good at and receive rewards from. In this case, the reward was gaining muscle and strength rather quickly compared to some of my friends that I trained with.

How Varied Are Results From Training?

When it comes to looking at research, it’s important to remember that we are often looking at mean (or average) outcomes. As in “Group A had significantly greater gains than Group B.” This would indicate that the group average of gains in Group A was greater than in Group B. It doesn’t mean that every single person in Group A had better gains than everyone in Group B.

It also doesn’t mean that if Group A added 50 lbs onto their max squat, every single person in Group A added 50 lbs onto their max squat. In reality, some folks probably added a decent more than 5, and some added significantly less.

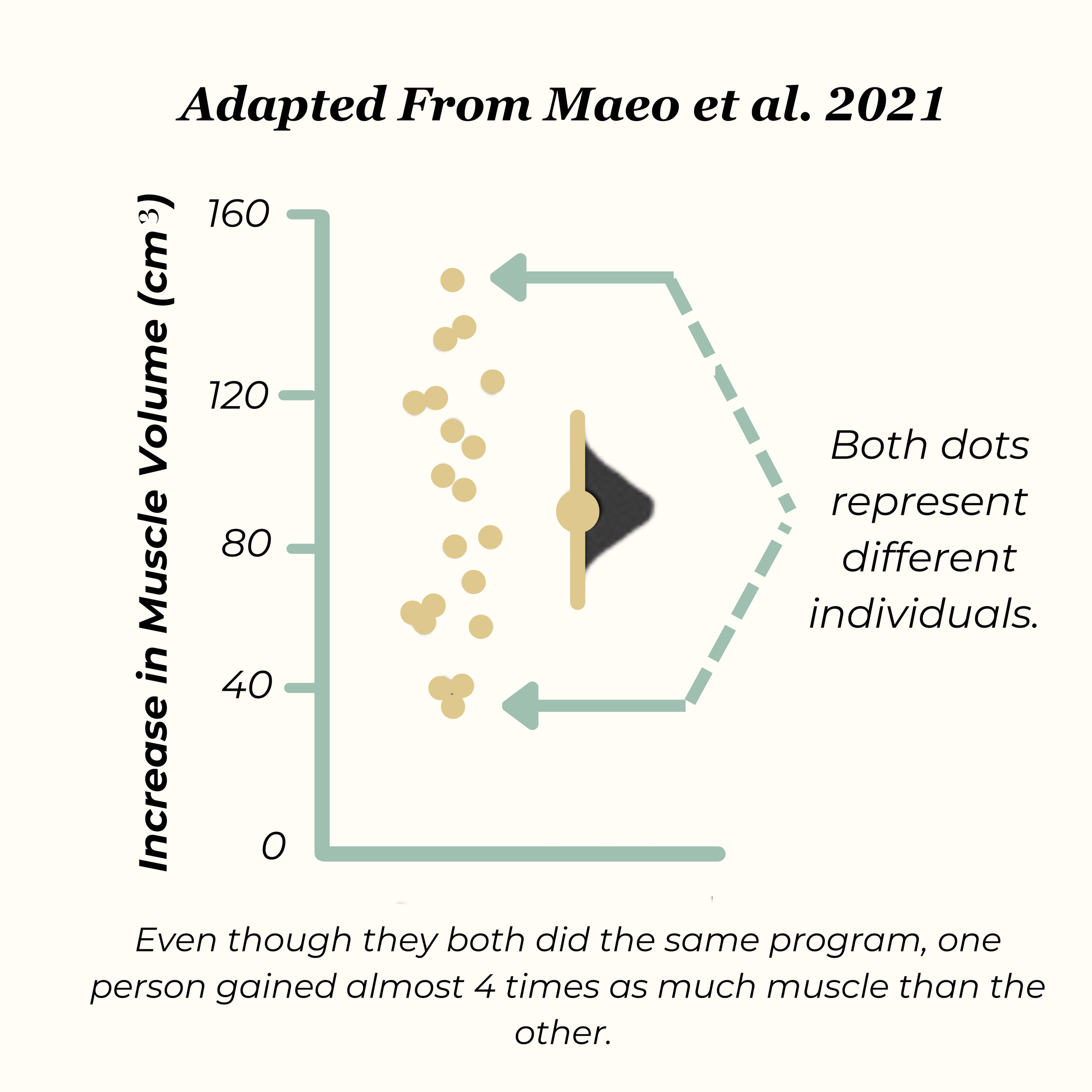

Responses do vary to what one may call an “unfair” degree. For two people of the same training experience doing the exact same program, one gains nearly 4x more muscle than the other. Which you can see was the case in this study by Maeo et al. (1).

Did the person at the top work four times harder than the person at the bottom? No. The training was supervised and standardized. That top responder is probably just more genetically inclined to gain muscle than the person at the bottom. Additionally, the protocol might have been better for that high responder, too. What’s optimal, on average, isn’t always optimal for everyone.

Being aware of this is helpful as that person at the bottom could be left feeling like they just didn’t work hard enough. In this case, given the control of this study, I don’t think this was the case. You can work equally hard as someone else and get significantly more or less results from said work.

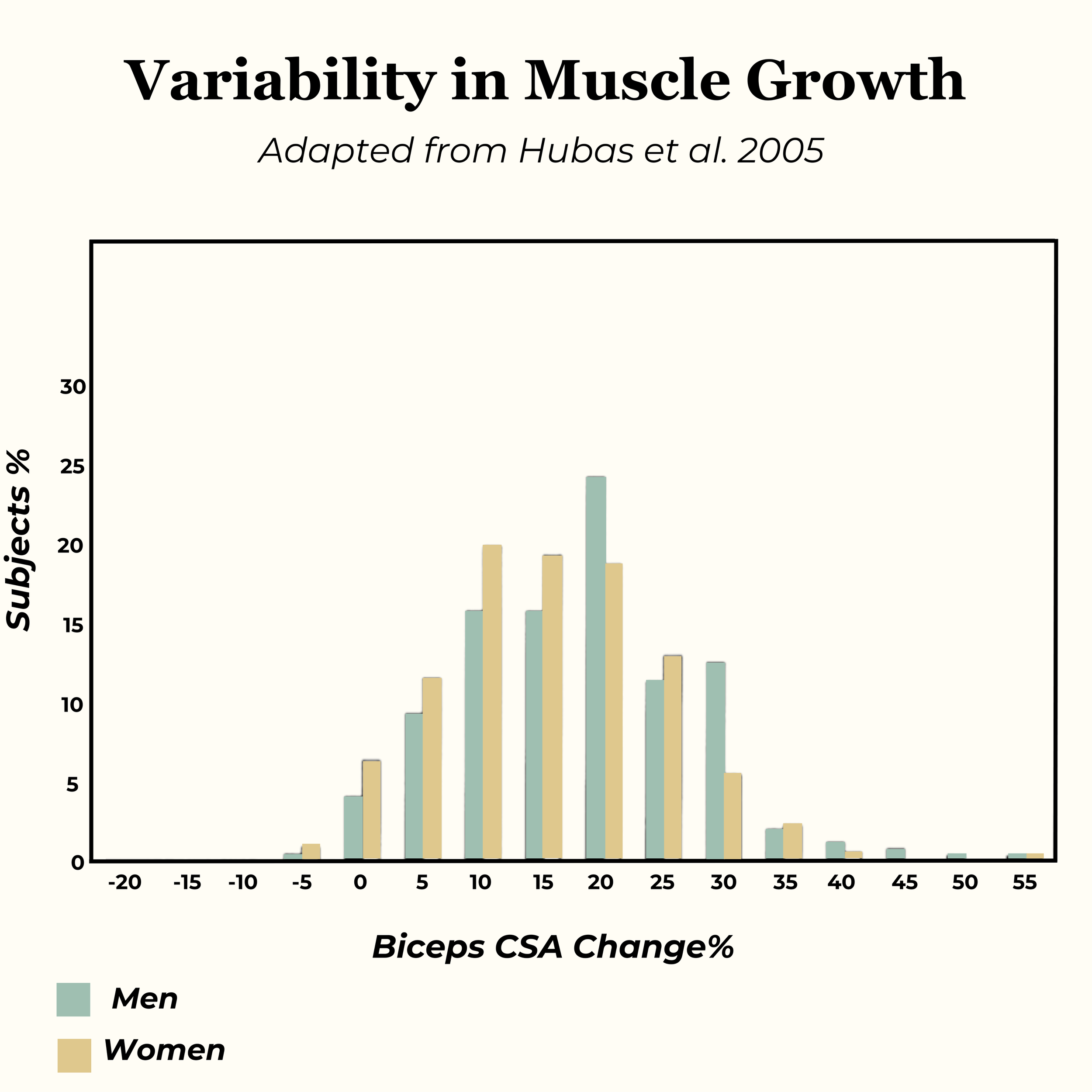

Another study by Hubal et al. (2) demonstrated just how varied this response can be in a much larger sample. 585 untrained mixed-sex adults did 12 weeks of resistance training on their non-dominant arm.

Unsurprisingly, muscle mass in the biceps and strength increased for both men and women. What was interesting was how wildly different some individual responses were.

39% of subjects gained 15–25% cross-sectional area of the biceps, which is a pretty solid response. While 10 subjects, making up the literal “One percenters” (1.7% to be exact, but who’s counting?), gained over 40% of the cross-sectional area.

On the other side, the results were those of Shakespearean tragedy. A very few unlucky folks literally lost muscle, and 6% of the subjects gained less than 5% of the cross-sectional area on their biceps.

When we look at averages and forget the individuals that make up these averages, we lose a lot of valuable nuance. It can also set unrealistic expectations of outcomes. Such as expecting that you will increase your biceps cross-sectional area by 15–25% after your first 12 weeks of arm training. That was the highest likelihood from a pluralistic perspective, but 61% of folks in this landed somewhere else in terms of gains or even losses.

One thing to also remember is that this specific protocol might not have been the optimal one for everyone. In fact, we know it wasn’t since. It’s safe to say it wasn’t optimal for those who gained less than 5% or even lost muscle. It’s also safe to say that it was probably closer to optimal for the folks who gained over 40% in their biceps CSA.

I’d say the higher responders likely have better genetics for building muscle than the lowest responders, but it also can be true that this protocol may have been better for them, too.

It is true there are “best practices” for building strength and muscle. Such as higher training volumes tend to yield greater gains (3) — to an extent, of course. That also doesn’t mean that everyone responds best to high volumes.

One study from Damas et al. (4) showed this. While higher volumes tend to elicit greater gains on average, ~36% of the subjects from this study got greater gains when doing lower training volumes. What was cool was that each subject did lower volumes on one leg and higher volumes on the other leg, making this a real comparison of responses to each volume for every individual.

Applying This Knowledge to Your Training

I think the biggest takeaway here is simply understanding that results vary, even when the effort is equal. This can help you understand why your training partner or friend gets better/worse results. Sure, they might just not be putting in as much/more effort than you. I’m not saying effort doesn’t matter. It does. I’m saying the outcomes don’t solely depend on said effort.

You’re not better for getting better results than anyone else, and you’re also not worse. That comparison can be inherently problematic as the variables may be very unequal. And if you train simply to be healthier and happier, this game can be detrimental as it may erode your enjoyment of training.

Secondly, what’s optimal on average may not be optimal for you. If the best evidence available says you should do X amount of volume to maximize gains in the gym, that’s not a bad place to start. It’s just also not the guaranteed place you will individually land.

You may respond better to more or less. Best practices are great guides on where to begin. You just shouldn’t get dogmatically stuck to them. Start there and tweak from there based on your results and response.

This will make your fitness journey more enjoyable and help you become a better problem solver with your own fitness goals. As opposed to strictly following protocols that don’t seem to be ideal for you and then getting frustrated with the outcomes.