The Power of Placebo

The key ingredient of the supplement industry?

10 min read

By: Dylan Dacosta

Sparknotes:

The placebo effect has been shown to have small to large effects on improving sports performance.

The largest effects come from more intense placebos, such as steroids, injections and even sham surgeries.

When navigating new supplements and workout fads, knowing the role of the placebo can help you make more informed decisions.

Stay curious, but also remain skeptical, especially regarding emerging trends in the fitness and health space.

When it comes to interventions to change human behaviour and even outcomes, one ingredient is overlooked by the average gym-goer. It’s not the force of hard work or discipline. It’s not the magic of the perfect morning routine. And no, it’s not even the *insert some secret THEY don’t want you to know*.

It’s the power of placebo, and its evil twin sibling, nocebo.

Placebo and nocebo refer to positive and negative expectancies' effects on your behaviour and outcome. This is why in research, you’ll commonly hear of there being a “double-blind placebo-controlled trial.” All this means is that both the researchers and the subjects were unaware of which groups/individuals were receiving the actual treatment or the placebo.

Even the researchers shouldn’t be aware since knowing might impact even the slightest of their behaviours, such as how they communicate with the trial participants.

A crass example of the placebo effect can be seen in Family Guy. A scene in which Brian (a dog with human-level cognitive abilities and a dash of alcohol dependency) gives Stewie (a baby with adult-level cognitive abilities) some apple juice and tells him it’s alcohol.

Stewie goes on to act drunk, which leads to him pouring out his heart to Brian with the classic drunk-guy “I love you, mannnn’s.”

I wanted to write about this because, within the fitness and wellness spaces, this effect gets ignored ubiquitously. Someone will try a new supplement that has promised them the moon and the stars. Then once taking it, they mobilize that belief into real action and start making meaningful changes that lead to the results they desire.

Then they attribute their results to something special in the supplement itself, not to any other effect that could be contributing. The issue with this analysis is that it ignores something that no seriously taken study would; the role of placebo in the outcome.

I also know this from my own experience. I’ve tried countless supplements and fads in my life. Whenever one worked, I believed it was the special sauce of the supplement I bought into, not the fact that I was also changing up my eating habits, working out more and dialling in on everything that would positively affect my results.

With this in mind, let’s talk about the placebo effect. How much of a role does it play, and how should we consider it when navigating our fitness and health journeys?

Let’s Talk Data

An excellent paper on this was a systematic review by Hurst et al. in 2019 (1) on the placebo effect in sports performance. It involved 32 studies and ~1500 people. 20 studies were nutritional placebos which included:

-Caffeine placebos

-Steroid/EPO hormones

-Amino acid placebos

-Beta-alanine placebos

-Fake supplement placebos

12 studies were mechanical placebos which included:

*Sham transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulations (those nodes placed on your skin, which send a low voltage electric current to try and help relieve pain.)

*Placebo Kin-tape

*Ischemic preconditioning placebos (a fancy word for repeatedly restricting blood flow to a limb, followed by allowing normal blood flow to return.)

*A placebo tennis racket (they were given a real racket, of course, but were told it was meant to increase serve velocity.)

*Cold water immersion

*Magnetic wristbands

In short, the placebo effect was very real and had varying effect ranges, depending on the type of placebo.

The overall placebo effect for nutritional placebos was a Cohen’s d effect size of 0.35. This is a small but meaningful effect. The overall placebo effect for the mechanical placebos was slightly higher at 0.47. This is still considered a small effect but is close to entering the “medium” effect range.

You’ll notice in the picture above that each sub-category had differing effects. This is partly due to the varying amount of studies and subjects but also because expectancy will generally impact the placebo effect.

Simply put, if you were given a pill (not knowing it was a placebo) and told that it would reduce your pain, similar to Tylenol, your expectancy would be low. If you were injected with something you were told would relieve your pain, similar to an epidural, your expectancy would likely be higher since the injection would be perceived as a more severe and effective treatment.

One of the most intense interventions you can have is surgery. So the expectancy of surgery would be pretty high. It’s just too bad we can’t do fake surgeries on folks to see how much of an effect placebo could have on interventions of that intensity.

There’s just no way fake surgeries are a thing. Right?

Right???

Wrong.

I found this fascinating, but sham surgeries are a thing. A meta-analysis was done by Jonas et al. in 2015 (2) on the impact of sham surgeries on improving outcomes compared to actual surgeries.

Above, you’ll notice active surgeries did better than sham ones. This was expected, but the effects were closer for some conditions than I would have thought. For GERD, the sham surgeries only improved symptoms about half as much as the actual surgeries, but for weight loss and reducing pain, the placebo effect was quite profound compared to the actual surgeries. This is limited data on a small number of types of surgeries, but it shows how much of an impact the placebo effect can have, especially when expectancies are high.

In conjunction with this, the first image from the Hurst paper corroborates the impact that expectancy can have succinctly. The steroid placebos had a very large effect, with a Cohen’s d effect of 1.44.

* Sidebar: a 1.0 Cohen’s d score shows that the mean score increased by one full standard deviation, which is rather large and shows the steroid placebo effect amongst the studies on weightlifting and running performance to improve scores one and a half standard deviations nearly. *

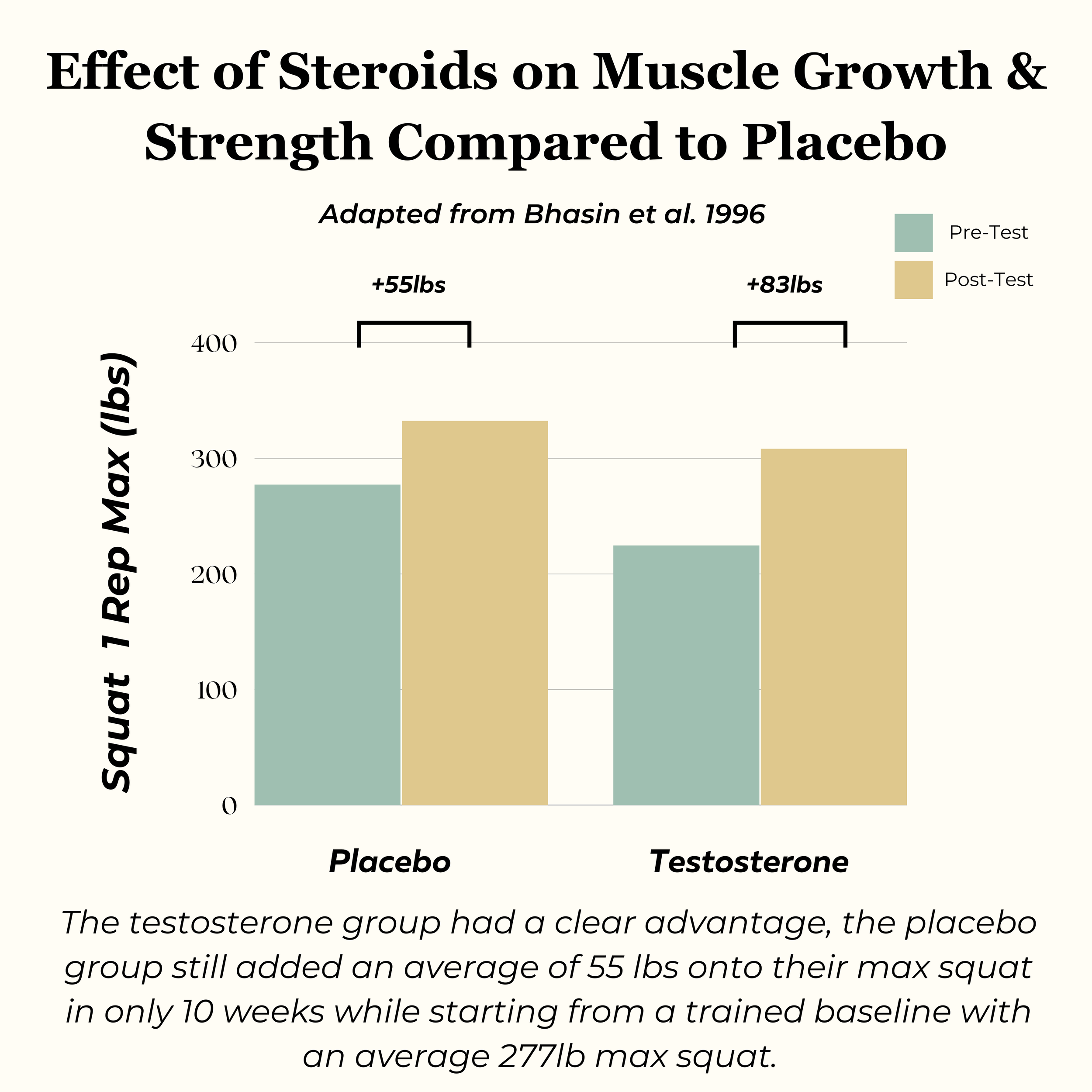

Additionally, a study from Bhasin et al. in 1996 (3) showed how remarkable steroids were for building strength and muscle in young men, but what was interesting was that for strength gains, the placebo group made some huge strides over the 10-week intervention.

The steroid group did better, but the placebo group added 55 lbs onto their one-rep max squat. It’s important to highlight that these guys had training experience prior, and their average one rep max to begin the trial was 277 lbs. Most trained guys with a ~275lb max squat ain’t adding 55 lbs onto that in 10 weeks. Or at least they aren’t without thinking they’ve been drinking some of Michael’s Secret Stuff.

Returning to the Hurst paper, it’s important to point out that some placebos were trivial or not impactful. All examples in the graphic above show at least a “small effect” (anything 0.2 or higher), but subcategories were less meaningful. The kin tape placebo showed nothing interesting. The ischemic preconditioning showed trivial to no effect, and the wristband placebo was ineffective. The beta-alanine placebos weren’t meaningful, and the sodium bicarbonate placebo was trivial.

The lower the expectancy of the placebo, the smaller the effect. Which tracks with steroids, EPOs nerve stimulations, delivering the largest placebo effect.

Can Placebo Impact Body Composition?

The above papers all measured sports/training performance. This begs the question, “To what extent the placebo effect can impact body composition changes?”

You could argue that if a placebo effect helped you train harder, you might be able to build more muscle or even lose slightly more fat, but I doubt those effects would be anything to get excited about. The placebo effect may wear off over time, especially since these adaptations take a long time. Regarding the steroid study by Bhasin, the steroid group had ten times more triceps growth and ~2.5 times more quad growth. The strength gains were closer, but the steroids clearly led to more muscle growth than the placebo.

Expectancy will also matter here, as I’ve mentioned an annoying amount of times by now. In one study by Tippens et al. in 2014 (4), the placebo subjects were given a pill and told it would “moderate cortisol secretion,” “increase fat burning and energy,” and would “reduce cravings,” which would make dieting easier. There was no difference in weight or waist circumference changes between the group told they were given the weight loss drug, the one told there was a 50% chance they got the drug or the placebo and the group given nothing.

The long-term outcomes mentioned above were bland. Still, some more short-term appetite and hunger data have shown that a placebo can impact hunger and satiety and even have a small effect on the hormones involved with hunger.

A study by Hoffmann et al. in 2018 (5) did show that the group given a satiety-inducing drug (that was a placebo) showed lower hunger ratings around an hour after the ingestion, even though they fasted. The hunger-inducing group had an increase in hunger, while the satiety-inducing group had a decrease in hunger. The satiety scores matched this with satiety increasing in the satiety-inducing placebo group and reducing in the hunger-inducing placebo group.

Interestingly, ghrelin levels (a hormone that increases the drive to eat) were slightly increased in the women in the hunger-inducing placebo group. This difference was significantly larger than the women in the controls. This only impacted women and wasn’t huge, but it showed that the placebo effect might affect our physiology, such as our hormones associated with hunger.

I will remind you this should be tempered because acute data doesn’t mean the long-term outcomes will be the same. In the Tippens paper, we saw that the placebo effect didn’t impact long-term weight loss over 12 weeks with a weight loss placebo tablet.

Circling this back to expectancies once again (and I promise for the final time,) the new weight loss drug, semaglutide, which I’m sure you’ve heard of (brand name: Ozempic), also has had some interesting data on the subject. While the drug itself seems to work, the placebo group in one of the trials lost an average of 5.7% of body weight from baseline after 68 weeks (6).

The actual drug group lost 10.3% more weight from baseline, losing an average of 16% of body weight from baseline over the 68 weeks. Those are tremendous results, but the placebo effect may have been responsible for one-third of the overall effect based on the placebo group outcomes. It’s also worth sharing that both groups received behavioural therapy throughout the intervention, so the placebo effect wasn’t doing all that work.

What to Do With This Information?

I wanted to write this to help you think more critically about how you engage with and interpret fitness and health information, especially considering how bombarded we are with deceptive marketing.

I often hear clients fall into the trap of thinking something is special because, for a period or because some effective yet misleading advertising has convinced them it helped them.

If you believe in something wholeheartedly, it’s likely going to have an impact on you. The issue is that impact can’t be directly attributed to a unique property in your supplement or fancy workout.

That effect could be mostly, if not all, placebo. It’s easy for this to be the case when we consider that plenty of supplements on the market have minimal to sometimes zero placebo-controlled trials on humans to back up their claims.

If a claim fits neatly into your desires, such as being told this pill will “melt away belly fat” while aiming for that specific goal, the placebo effect is almost primed to be potent. In this case, this belief can be mobilized into action. The action would lead to the results, not the actual supplement. Understanding this while also knowing the severity of the placebo effect can be a substantial cash-saving defence for you.

As someone who has spent far too much time and money on supplements and fads that were utter rubbish simply because I was duped and also wanted to believe what the shady salesperson told me, I have deep empathy for falling into this trap.

If I had been more aware of the placebo effect and how to factor it into my decision-making, I would have saved a lot of cash and time.

Lastly, this doesn’t mean you should oppose trying anything. If you want to try something, find some cited evidence to back it up first (examine.com is an excellent resource for supplements) or at least head into it with a skeptical mind. This doesn’t mean saying, “This won’t work,” either. It means trying to be as neutral as possible and also not changing up everything else at the same time. If you do, you might attribute the results you got from your hard work to some particular fad or supplement. In reality, it was you that got those results.

I want you to feel more confident in yourself and your capabilities, not in some external factor, especially when that external factor is a shady supplement or new workout fad that preys on your frustrations or ignorance.

Cheers,

Coach Dylan 🍻

References:

1 . The Placebo and Nocebo effect on sports performance: A systematic review

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31414966/

2. To what extent are surgery and invasive procedures effective beyond a placebo response? A systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized, sham-controlled trials

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4679929/

3. The effects of supraphysiologic doses of testosterone on muscle size and strength in normal men

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8637535/

4. Expectancy, self-efficacy, and placebo effect of a sham supplement for weight loss in obese subjects

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4182347/

5. Effects of Placebo Interventions on Subjective and Objective Markers of Appetite–A Randomized Controlled Trial

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6305288/#:~:text=Our%20randomized%2Dcontrolled%20double%2Dblinded,increased%20ghrelin%20levels%20in%20women.

6. Effect of Subcutaneous Semaglutide vs Placebo as an Adjunct to Intensive Behavioral Therapy on Body Weight in Adults With Overweight or Obesity: The STEP 3 Randomized Clinical Trial

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33625476/