What We Get Wrong About Stretching

Study review looking at the effects of a 6 week static stretching protocol on flexibility and strength

Spark Notes

After 6 weeks of a static quadriceps stretching protocol, the stretching group saw significant improvements in knee flexion range of motion, rates of force development and strength endurance in the quadriceps.

Stretching was done 3x per week for 6 sets of 30 seconds per session.

Stretching for a few seconds whenever you feel tight is practically the same thing as curling a dumbbell once every time you feel weak.

While intense static stretching right before you lift is probably not ideal, lifters don’t need to avoid static stretching completely and could perhaps see benefits from it.

If you want to see increases in flexibility, following a consistent stretching protocol is key. You should apply the principle of progressive overload within the context of your flexibility training to make sure you’ll elicit an adaptation.

When it comes to stretching, there is no short of confusion out there.

Some people think stretching will significantly mitigate injury risk, while some think that static stretching before we lift will kill all of our gains.

Regardless of what your views are on stretching are, one thing is for sure; navigating this topic is confusing.

The reason I wanted to talk about stretching is because from my observations, I think a lot of us are stretching wrong.

That may sound like a weird thing to say, but hear me out.

I myself and people I know, often stretch what feels tight, when it feels tight.

Your hamstrings feel tight so you hold a nice stretch for a few seconds. Or your hips feel tight, so you stretch out your hip flexors for a bit. Then voila — you feel better.

There is nothing inherenetly wrong with this either. Stretching after sitting for a while is a perfectly reasonable thing to do. If you live with a cat or a dog, you’ll notice they probably stretch immediately upon rising.

The issue with this, is that it doesn’t actually do anything.

Aside from feeling better, you’re not really going to get anything out of this in regards to improving flexibility in the long term. Which is not me saying that you shouldn’t stretch when you feel stiff or after you’ve been sedentary.

This is me saying that reactively stretching every time you feel tight, for a few seconds is basically the same thing as picking up a dumbbell and doing one curl every time you feel weak.

You can imagine the latter example will not lead to much strength and hypertrophy gains. Just like the former won’t meaningfully increase your flexibility.

If you want to get stronger and build muscle, you may know that you will need to adhere, in some way, shape or form, to the principle of progressive overload.

In it’s simplest terms, this means adding more weight, volume or generally more stimulus to a given muscle or movement overtime to elicit an adaptation response — the adaptation being gaining strength, skill or muscle here.

What people mistake about stretching, is that the same rule applies.

If you want to increase flexibility of a muscle, you’re going to have to place said muscle through a stressor it will have to adapt to.

In other words, you’ll need to apply progressive overload to your stretching.

This brings us to a study I wanted to cover briefly.

Study reviewed: Effects of 6-Week Static Stretching of Knee Extensors on Flexibility, Muscle Strength, Jump Performance, and Muscle Endurance

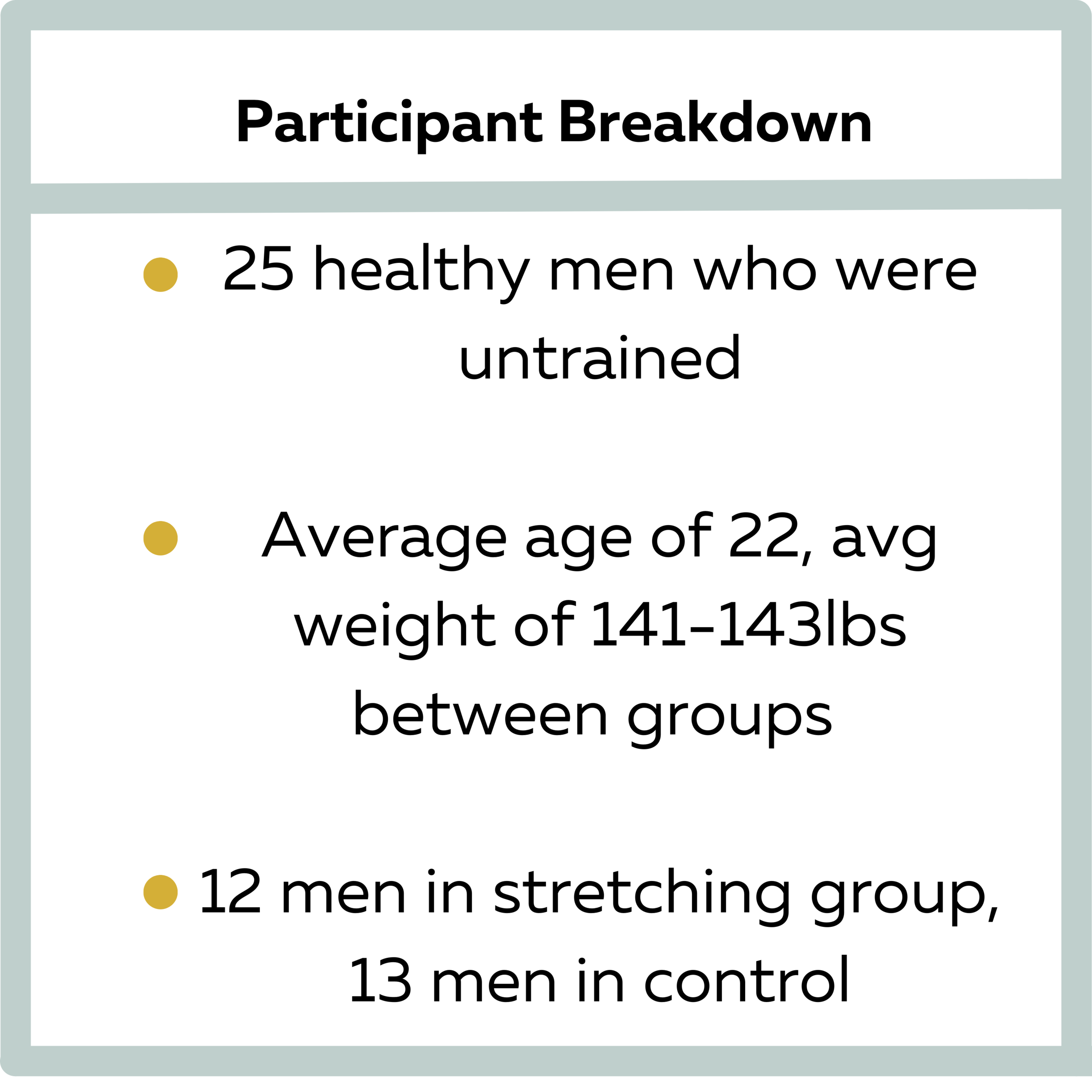

This was a 6 week study comparing a stretching group to a control group who did nothing. All subjects were untrained.

The stretching group was made of 12 men and the control group of 13. Making this a small sample size. Meaning we should not make bold claims from it.

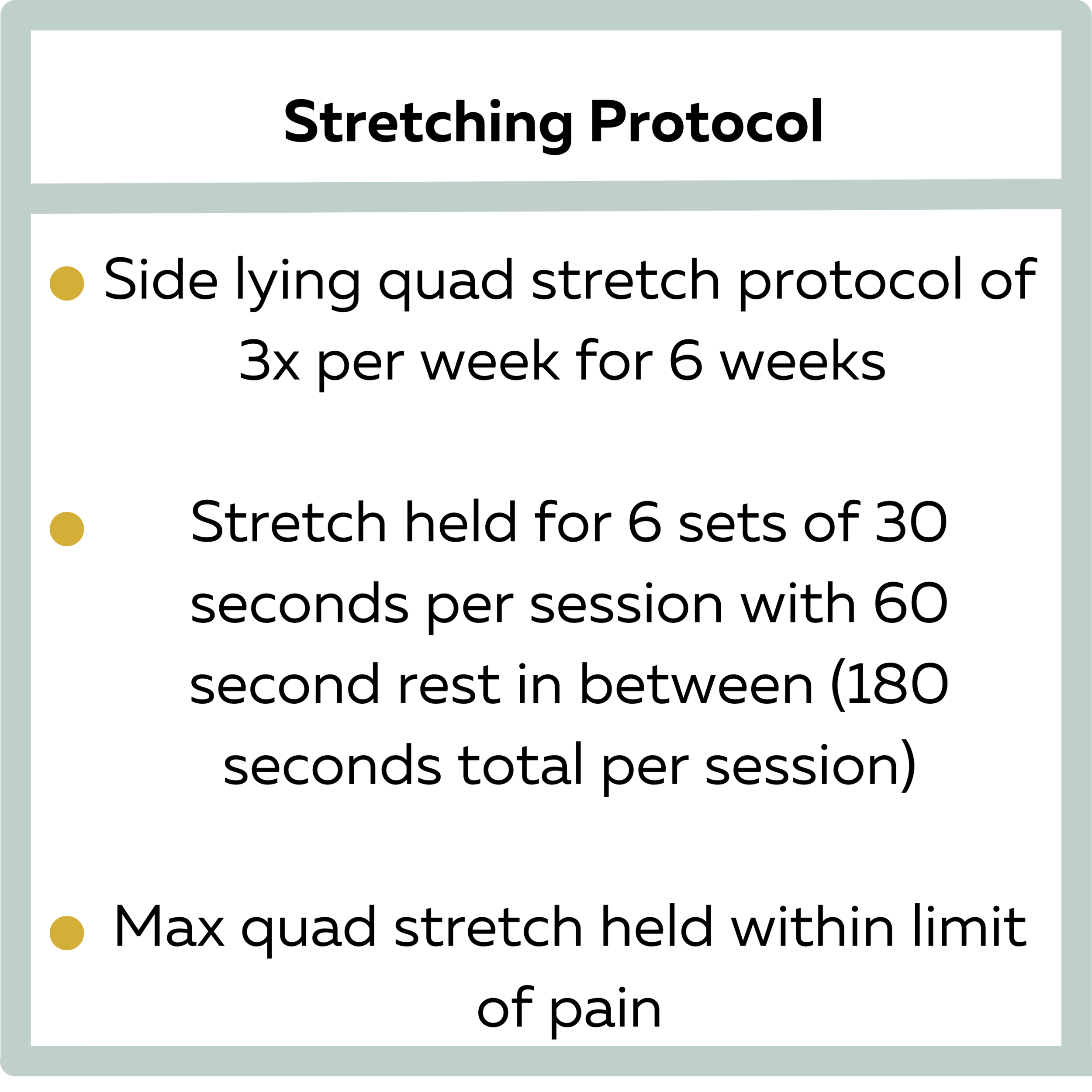

The stretching group would go through a 6 week stretching program where subjects would stretch their quads for 3 sessions per week. Each session would consist of 6 sets of 30 seconds, with a 60 second rest in between.

Subjects would lay on their sides and pull their top foot back to their rear while keeping their hips at zero degrees. Sounds overcomplicated, but just imagine stretching your quad while laying on your side.

Here is the list of measurements taken before and after the 6 week trial in both groups:

Knee flexion range of motion

Maximum voluntary isometric quad strength

Rate of force development in the quads

Squat jump height

Counter movement jump height

Rebound jump index

Strength endurance of the quads

Results

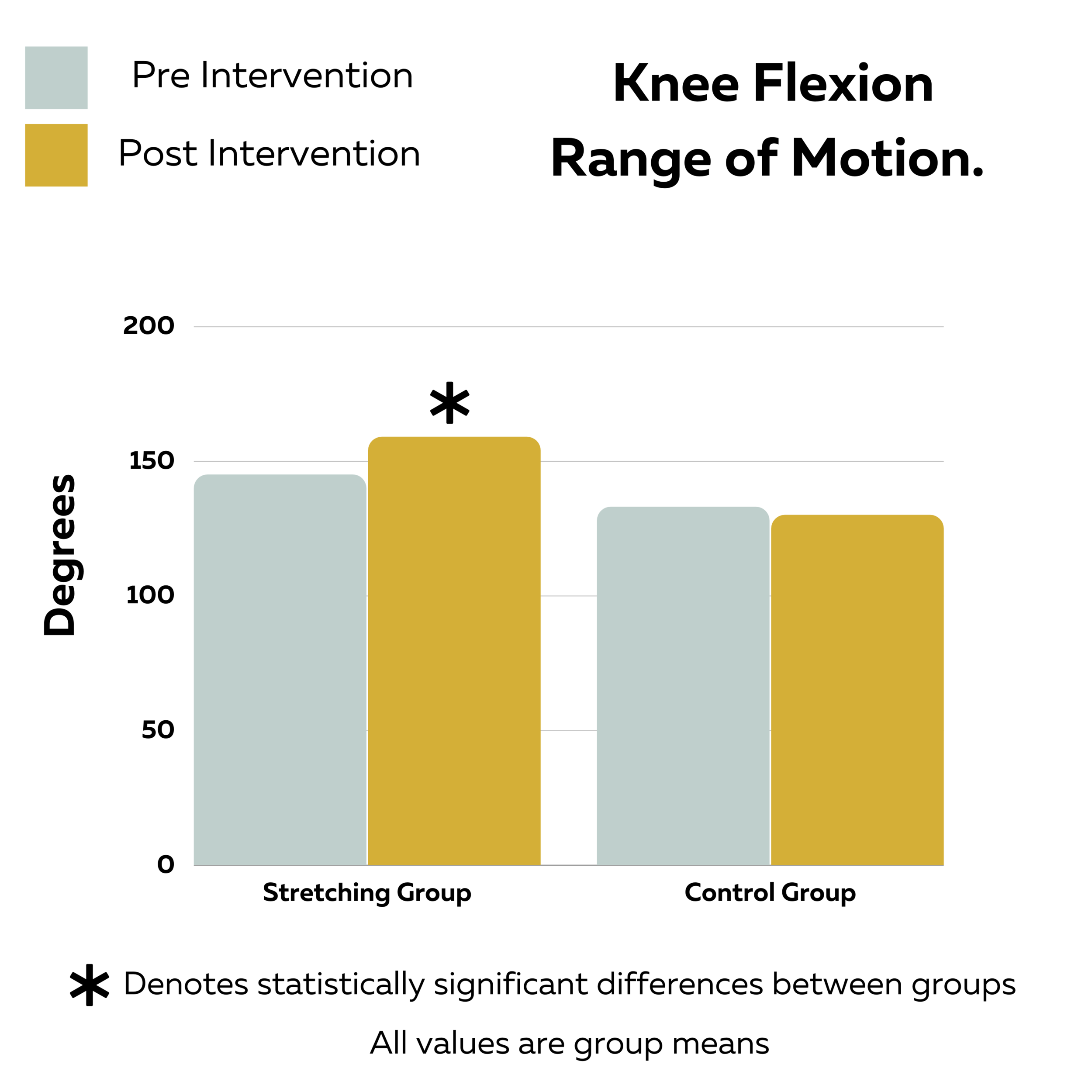

After 6 weeks, to no surprise, knee flexion range of motion increased significantly in the stretching group and held steady in the control group.

The stretching group gained an average of 14 degrees of knee flexion range of motion while the control group actually lost an average of 3 degrees of knee flexion range of motion.

When it came to jump performance, there was no significant improvements or drop offs in either group.

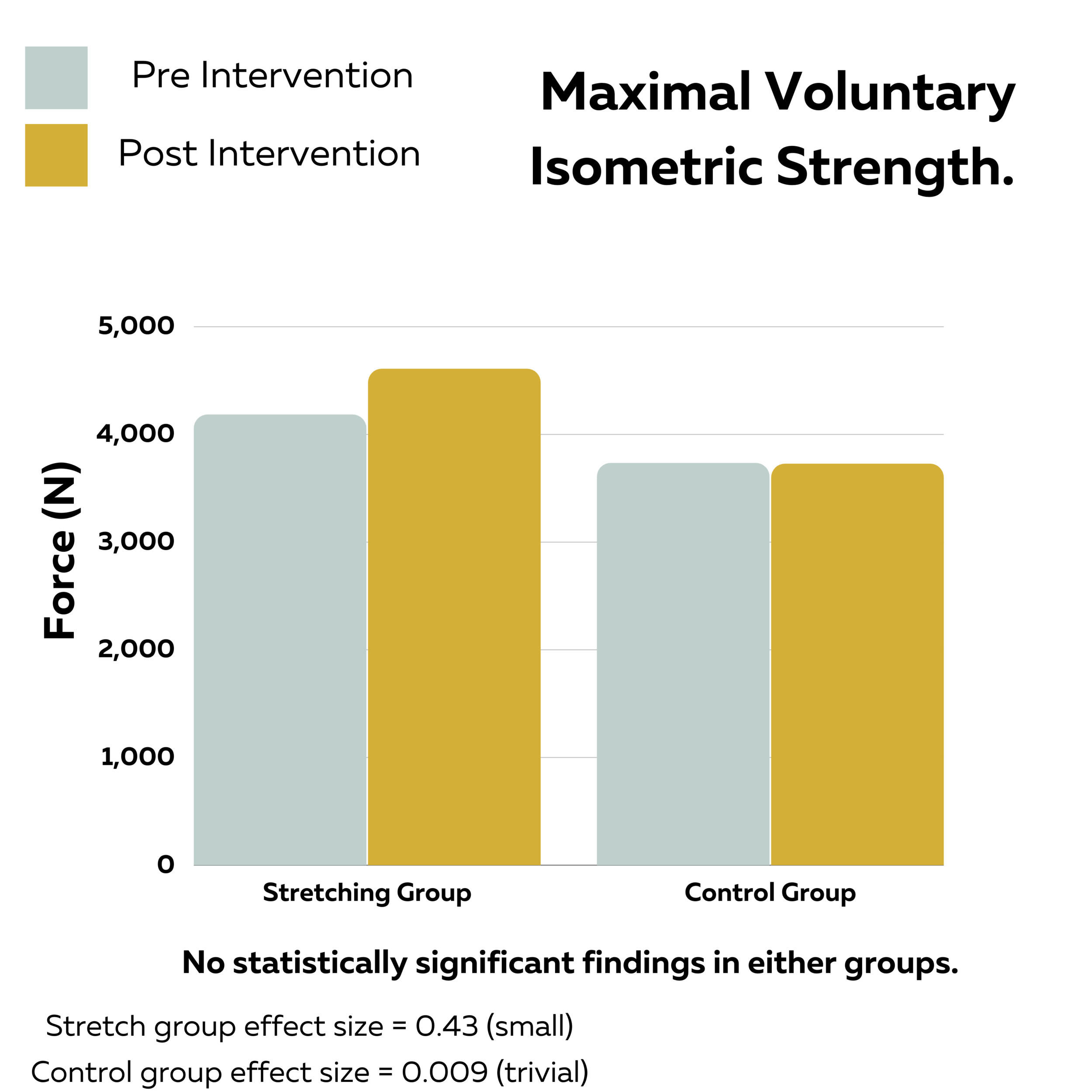

For strength, there was an insignificant increase in maximum voluntary isometric strength in the stretching group. Although the findings were insignificant (which may be due to a small sample size + a large standard deviation), the effect size was 0.43 which would be considered on the high end of a “small” effect. Also, the rate of force development did increase significantly in the stretching group with a “medium effect” of 0.69.

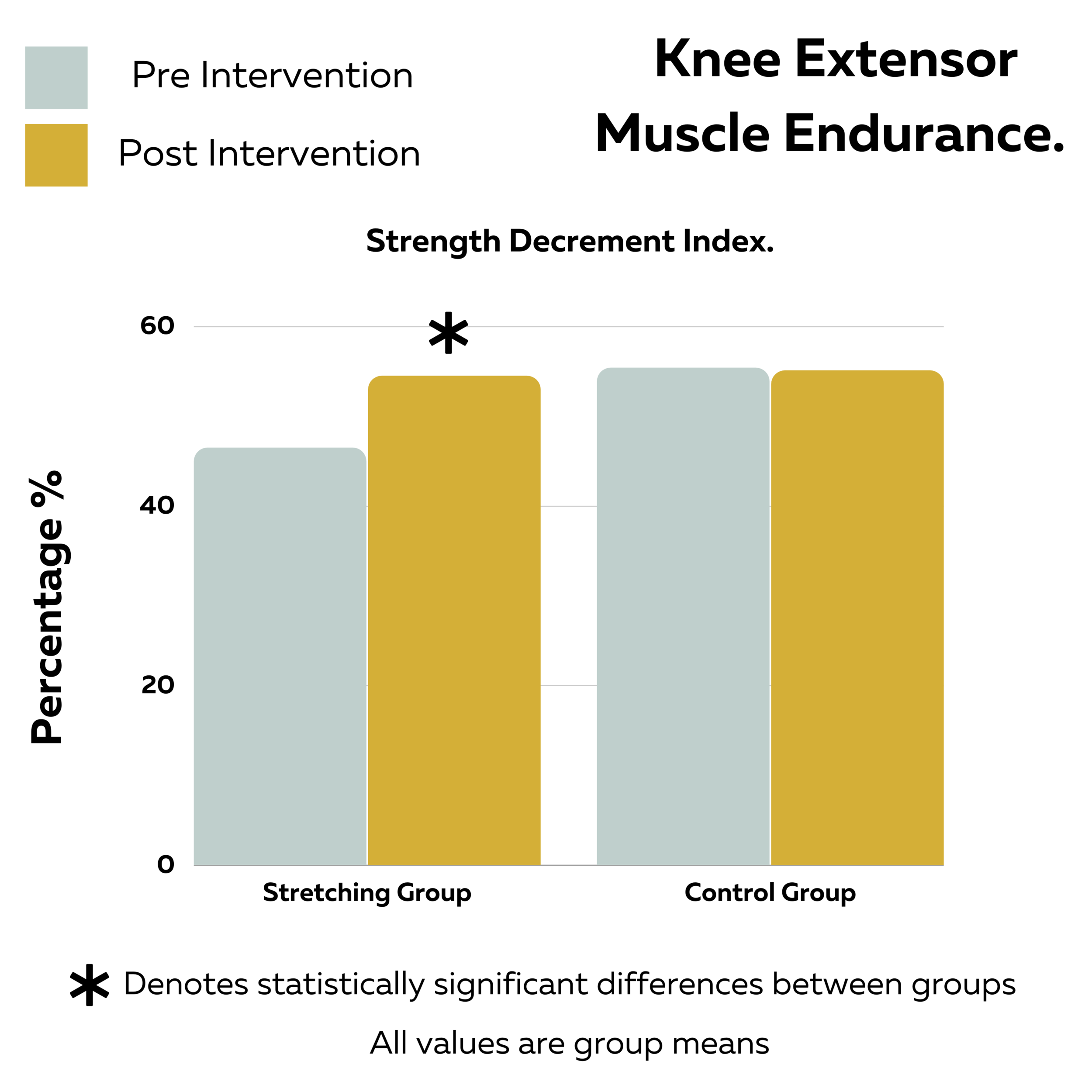

Lastly, for strength endurance, the stretching group saw a significant increase in endurance while the control group did not. The graph may be confusing, but simply put, the subjects did 50 reps on an isokinetic leg extension (one where the rep speed doesn’t change regardless of force produced into it). Workload was calculated for the first 17 and last 17 reps to determine losses in strength. Below you’ll see that from before the trial to after, the stretching group saw an increase in muscular endurance.

Applications

To circle back to the title of this article, this is what I think we get wrong about stretching. There is a lot of debate about stretching within fitness, but I genuinely haven’t encountered many folks who stretch like what was done in this study.

Stretching as I mentioned before, often looks like just randomly stretching a muscle that feels tight for a few seconds. Which seems like a hardcore neutral approach. By that, nothing positive or negative will come from that.

Stretching does work to increase range of motion. We just need to stretch in a similar manner to how we make strength or performance gains. By following a protocol, being consistent and making sure progressive overload is being applied.

This could look like what was done in this study or you can try different approaches. The key thing to ask yourself is:

“will my body need to adapt to this approach?”

If the answer is no, then your body probably won’t adapt. I’ll tell you for sure, that it won’t be adapting to randomly being yanked on when you feel tight.

If you do want to increase flexibility because you lack range of motion, follow a protocol that will increase in duration or intensity over time.

I know this sounds boring, but you can do this while watching TV to make it less of a snooze.

This approach has benefitted other muscles and joints too. A common “tight” area for people is in the ankles, or more appropriately the calf muscles. One study had 13 runners stretch their calves for 4 minutes in the morning and 4 minutes in the evening for 8 weeks. After 8 weeks, the ankle dorsiflexion range of motion tripled on average (from 5 degrees -15 degrees).

8 minutes a day may sound like a tall order (and it probably is), but the key was they stretched consistently and for a decent duration. Not just randomly pulling a muscle for 10 seconds.

So if you want to increase your flexibilty, stretching is a great option. Just remember that you should be following some sort of protocol instead of randomly stretching.

If you absolutely hate static stretching, there is evidence that strength training can have similar effects on range of motion increases as static stretching can. The key piece of context here is that you could only really expect ROM increases from strength training when being loaded at long muscle lengths.

ROM= range of motion

Think of a Romanian deadlift where you’re actually being loaded a in deep hip flexion (and also feeling a deep stretch on the hammies).

You shouldn’t expect the same range of motion gains in the hamstrings from the lying leg curl, since you’re not loading the hamstrings at a long or stretched muscle length.

Lastly, if you’re a lifter and avoid static stretching right before lifting (for good reason) this doesn’t mean you should avoid it all together.

The subjects here were untrained, but the chronic stretching only had positive outcomes on performance in this study. So static stretching could still be useful for you. Just perhaps avoid doing intense static stretching right before you lift in favour of low intensity stretching or even dynamic stretching of whatever muscles you’re about to train.

Happy lifting, or should I say, happy stretching!

Cheers,

Coach Dylan 🍻

References:

1. Effects of 6-Week Static Stretching of Knee Extensors on Flexibility, Muscle Strength, Jump Performance, and Muscle Endurance

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30161088/

2. The effect of calf muscle stretching exercises on ankle joint dorsiflexion and dynamic foot pressures, force and related temporal parameters

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21944945/

3. Strength Training versus Stretching for Improving Range of Motion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33917036/

4. Different volumes and intensities of static stretching affect the range of motion and muscle force output in well-trained subjects

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31464179/

5. Effects of static stretching for 30 seconds and dynamic stretching on leg extension power.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16095425/