Exercise Kind of Sucks For Weight Loss (But You Should Still Do it)

Those extra calories you burn in the gym may not be as helpful as you think.

By: Dylan Dacosta

10 min read

Spark Notes:

Exercise as a stand alone strategy for weight loss seems to be quite ineffective, on average.

One reason for this is that higher levels of active energy expenditure tend to get compensated back to varying degrees. So if you burn 400 calories in a workout, that may only contribute an additional 300 calories to your total daily energy expenditure. 100 calories would be compensated back somehow throughout the day in this example.

Exercise is still fantastic for our overall health and should absolutely be a part of any weight loss or health journey.

Even though exercise may not be the most effective strategy for weight loss on it’s own, it’s particularly important to help retain muscle mass (resistance training, especially) during weight loss and for increasing your likelihood of achieving weight loss maintenance.

Although exercise is often overvalued for weight loss, it seems to be undervalued for all the other benefits that it brings to our health.

When it comes to weight loss, exercise is one of the most common interventions that is taken to support this goal. In fact, some folks only exercise as a way to get and keep the weight off.

Don’t get me wrong, there has been plenty of people who’ve seen success with this strategy, but I want to address the elephant in the room.

Which is how ineffective exercise alone is, when it comes to achieving weight loss, on an average basis.

You most likely know or have been told that weight loss will be governed by energy balance. So getting into a negative energy balance will be needed if you are aiming to lose weight and more specifically, body fat.

There are two very simplified ways to you can do this:

Eating Less (less energy in)

Moving More (more energy out)

I mention simplified above because although this seems simple on paper, the interplay between these two variables is quite complicated.

In today’s article, I’m going to talk about the “moving more” side of the equation as a focal point, since you know, we’re talking about exercise’s impacts on weight loss.

In theory, if you kept your energy intake stable and increased your activity, you should lose weight. Yet, this often does not happen, or at least, does not happen to the degree in which we’d expect.

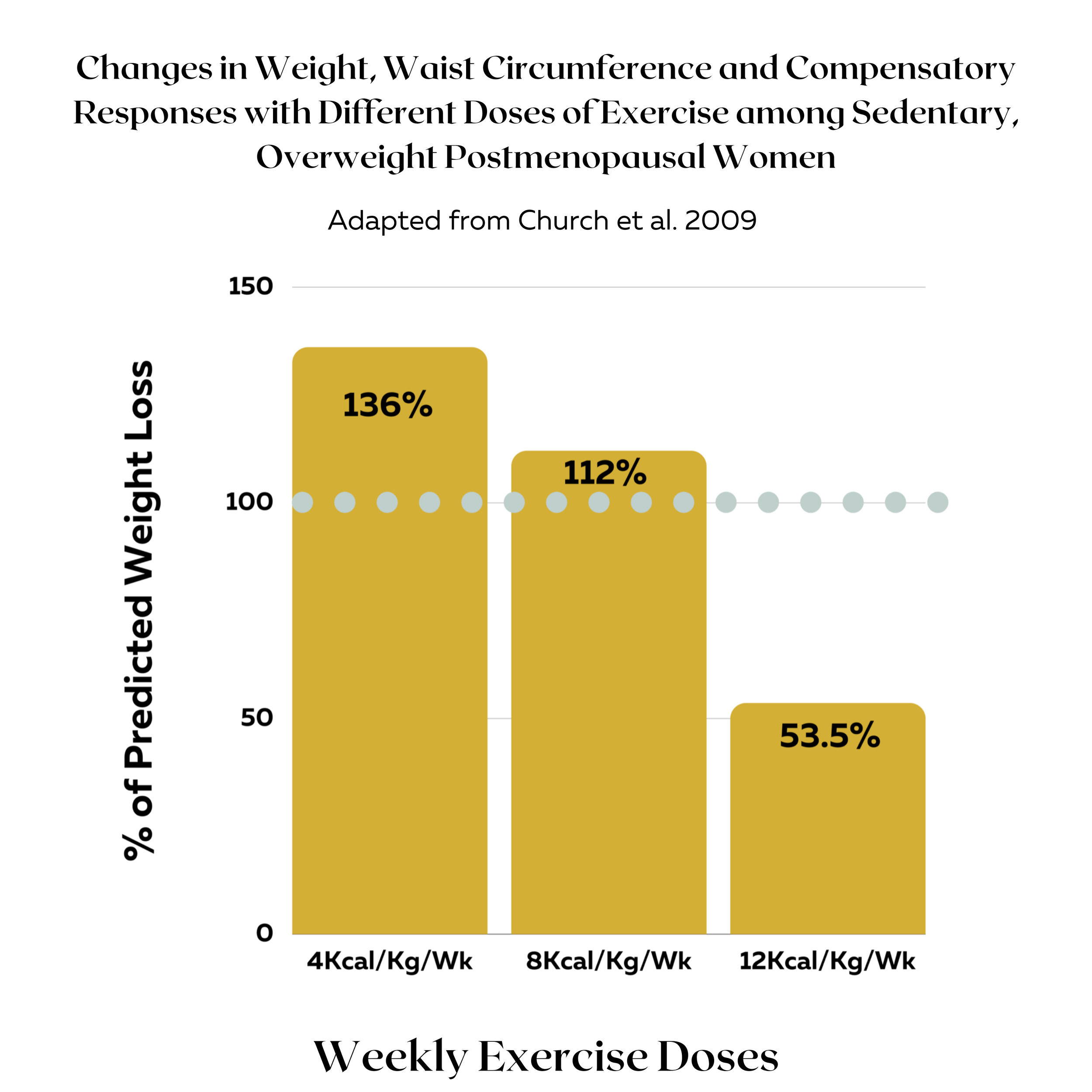

Burning 4 calories per KG of body mass per week

Burning 8 calories per KG of body mass per week

Burning 12 calories per KG of body mass per week

What we would expect is for the highest doses of energy burned from exercise per week to yield the most weight loss over the 6 month trial. Yet, we didn’t see that at all and tended to see the opposite.

Above you’ll see that the 8 cal/kg/bw per week group lost the most body mass and the 4 and 12 groups lost about the same. Even though the 12 cal/kg/bw group burned 3 times more energy in their weekly workouts.

Based on the predictions, the 4 cal and 8 cal group actually lost more weight than predicted, but the 12 cal group (the one who did the most exercise) drastically under performed. Only losing 53% of the weight they were predicted to.

So what happened? If energy out clearly went up, they must have eaten more to negate the amount of total weight lost. But in this paper, self reported energy intake actually went down from baseline to follow up in all groups.

*With that being said, we as humans truly suck at estimating our energy intake, so this should be taken with a large grain of salt.*

On the counter, I doubt their reported energy intake was so far off to explain the entire 47% less weight loss than predicted. What is more likely, is that the body actually compensated the energy out part of the weight loss.

What do I mean by this?

Well, we typically think of exercise calories we burn as being additive to our total energy expenditure, but this has been challenged quite a bit over the last few years. A counter idea of the constrained model has been put forth and could help explain some the lacklustre results that exercise tends to have as a stand alone method for weight loss.

This brings me to an interesting paper that examined a large amount of daily energy expenditure data to see if, as active energy expenditure increases, how it impacts total energy expenditure.

In theory, if the additive model were completely accurate, as active energy expenditure increased, basal energy expenditure would remain constant. As you’ll see below.

What was actually found was that, as active energy expenditure increased, there was a negative slope for basal energy expenditure. This indicates some form of energy compensation as active energy expenditure increased.

Before you start thinking activity is useless for increasing energy expenditure, remember that this slope didn’t show that activity was fully compensated for. Rather, just partially compensated for.

It’s also with noting this data was not taken from controlled exercise studies, but rather from a free living folks who had their energy expenditure calculated via doubly labelled water which is considered a gold standard technique due to it’s accuracy, while not having to constrain the subject to a tightly controlled environment. The basal energy expenditure was more precise and was gathered from respirometry measurements to calculate resting energy expenditure through measuring the gas exchanges (oxygen uptake vs carbon dioxide expelled).

This paper concluded the following:

One thing to note here is that there is plenty of variance in the degree of compensation between individuals. Similar to how there are individual responses to reducing calories or to overfeeding, there also seems to be a varied individual response to activity when it comes to energy compensation.

Here you’ll see some data on individuals from that paper. This was a sub analysis done on 68 elderly subjects aged 70–90 years old. It showed there was a moderate negative correlation between active energy expenditure and basal energy expenditure (r = -0.58) on average.

*An r value is a measurement of correlation between two variables. In this case, there was a negative correlation within individuals with active energy expenditure and basal energy expenditure. Meaning that as active energy expenditure increased, basal energy expenditure tended to decrease on average. An r of 1 or -1 indicates they move respond to one another completely. Example, if for every additional 100 calories of active energy expenditure done there was 100 calories of basal energy expenditure reduced, this would indicate an r value of -1. So the r value here shows a moderate negative correlation of between these two variables of -0.58.*

The grey dots represent the individual data points and the black lines are the slopes for those individual data points. You’ll see here that some folks had essentially no compensation, while others had even greater degrees of it when expending more active energy. For those who compensate less, exercise will likely be more effective for weight loss than for those who compensate greater.

*It’s also key to remember that data was specifically on older folks and not in a tightly controlled study, so this is not the definitive proof for how much any individual will compensate with higher activity levels.*

Ok, So Exercise May Not be Great For Fat Loss. Should I Abandon It Then?

This is where some folks get into trouble. The answer to this question is an astounding “hell no!”.

This would be an example of black and white thinking. In short, nothing above implies that exercise does nothing for weight loss. Rather, it seems that we may be overvaluing the role of exercise as a stand alone strategy for weight loss. Meaning we probably shouldn’t be adopting exercise-only interventions for weight loss.

Not to mention that exercise has a legitimate laundry list of health benefits outside of weight loss.

With all of this in mind, one thing to note is that resistance training during weight loss will help maintain or even help build muscle mass while you lose fat. Making strength training a staple that I recommend during an intentional fat loss goal.

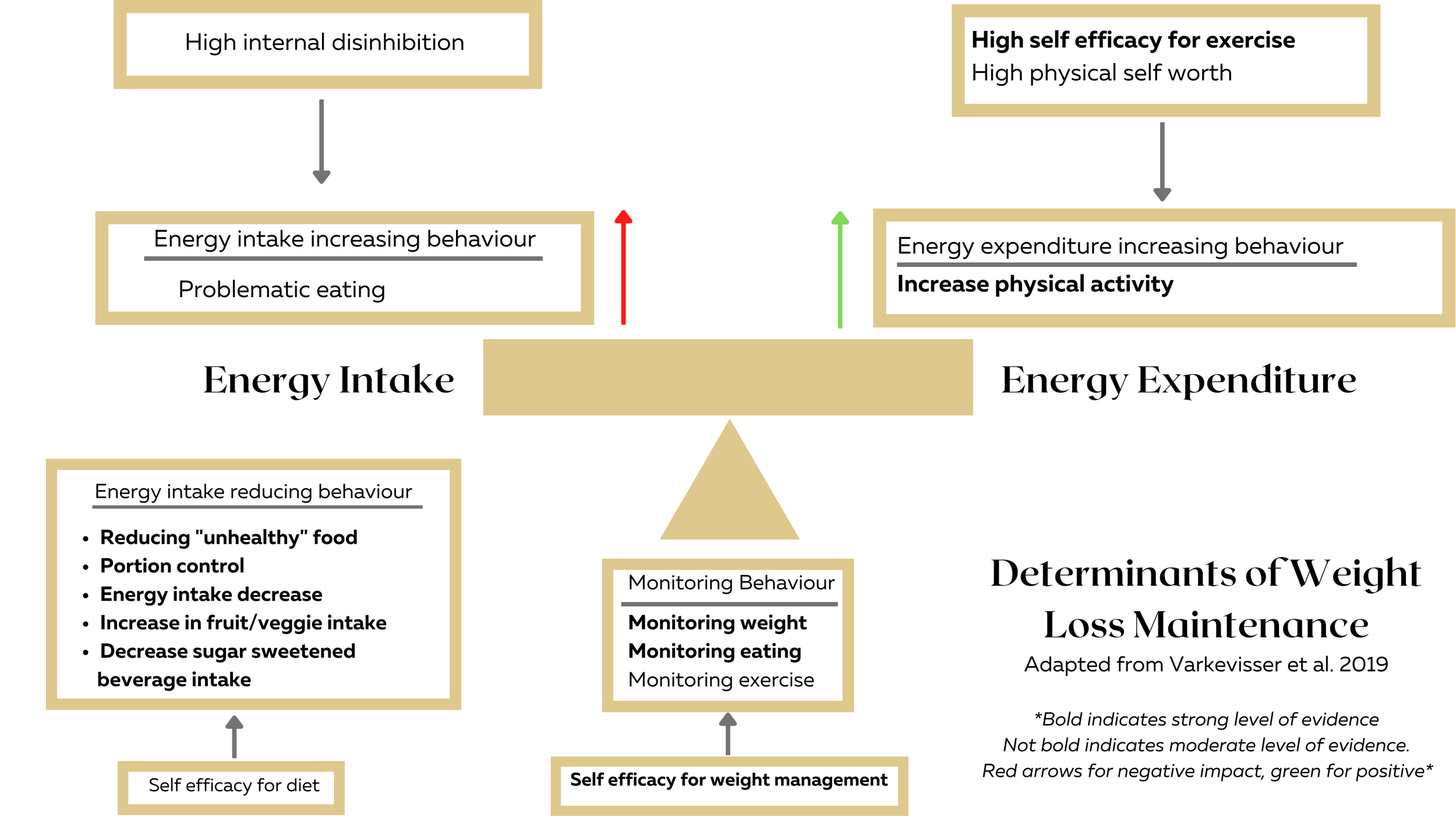

Another thing to note is that exercise seems to be helpful when it comes to achieveing weight loss maintenance. And if you haven’t read my previous work on the struggles of weight loss maintenance, you can check that out here.

Above you’ll see an image that was adapted from this systematic review looking at the determinants of weight loss maintenance. Where high self efficacy for exercise had strong evidence as being a determinant for weight loss maintenance, along with increasing physical activity. Also, monitoring exercise had moderate evidence to support being a determinant of weight loss.

Secondly, a systematic review looking at successful weight loss maintenance(losing 10% or more of body weight is often the most common metric for successful weight loss maintenance) showed that exercise was the most consistent positive correlate for weight loss maintenance.

Lastly, if we look at diet alone or diet plus exercise interventions for weight loss, the combination of both diet + exercise has been shown to have greater outcomes than diet alone interventions for weight loss. While the differences weren’t huge (1.14 kg greater for D+E than for diet alone), they did favour the combined groups and that was only measuring weight loss. Some of the interventions included in that meta-analysis did have resistance training as a part of the exercise protocol. So it’s likely the subjects retained more lean mass and perhaps lost more fat mass as a result.

Applications & Takeaways

Exercise alone is likely not as helpful as an independent strategy for weight loss, as you may think. This seems to be at least partially explained by the fact that energy compensation tends to happen when you burn more energy from exercise.

One study found that 28% of active energy expenditure to be compensated for on average. If this were true for you, out of say, 300 calories that you may burn from a workout, only about 216 calories would be added onto your total energy expenditure for the day.

It’s key to remember, there is a high amount of individual variability here. You may compensate more or less. If exercise easily helps you drop weight, you may compensate less. If extra exercise seems to do nothing for you in terms of resulting in weight loss, you may be someone who compensates more.

When it comes to weight loss, managing your diet should typically be your top priority. Think of managing your energy intake as, Batman while your physical activity is more like, Robin. Robin is still helpful, but not that effective on his own.

Regardless of all of this, exercise is fantastic for you and should absolutely be a part of your lifestyle for overall health. Even though it’s overvalued for weight loss directly, I think we really undervalue it for overall health.

Where exercise seems to be most beneficial in this context, is for helping preserve lean mass as you lose weight (mostly through resistance training) and increasing likelihood of achieving weight loss maintenance — which can be a real pain in the ass.

Final thoughts: Exercise is awesome. Just not as a stand alone strategy for weight loss, on average.

Cheers,

Coach Dylan 🍻

References:

1. Changes in Weight, Waist Circumference and Compensatory Responses with Different Doses of Exercise among Sedentary, Overweight Postmenopausal Women

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2639700/

2. Constrained Total Energy Expenditure and Metabolic Adaptation to Physical Activity in Adult Humans

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4803033/

3. What is the Doubly-Labelled Water Method?

https://doubly-labelled-water-database.iaea.org/about

4. Energy compensation and adiposity in humans

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34453886/

5. Determinants of weight loss maintenance: a systematic review

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7416131/

6. Successful weight loss maintenance: A systematic review of weight control registries

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32048787/

7. Long-term effectiveness of diet-plus-exercise interventions vs. diet-only interventions for weight loss: a meta-analysis

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19175510/