Metabolic Adaptation: The Body’s Defence to Fat Loss

Study review on metabolic adaptation to significant weight loss.

Key Points:

After significant weight loss, your metabolic rate is expected to drop as a result of lower body mass.

The present study did show evidence that at a certain point of weight loss, this reduction becomes greater than what would be expected. This could be defined as adaptive thermogenesis.

After two phases of losing 5kg of bodyweight, the group of men in this study demonstrated enough metabolic adaptation that what was expected to be a 700 calorie deficit per day, resulted in a full weight loss plateau.

Metabolic adaption is not completely avoidable, but there are strategies to you can apply that may help avoid hitting such a harsh weight loss plateau,

Read below to find out more!

The weight loss plateau. Everyone who has lost a significant amount of weight has probably come into contact with this nuisance.

You’re following your diet, seeing results and feeling great about your plan.

Then, all of the sudden, what was working before, simply stopped working.

Now, there are plenty of cases in which someone is being less compliant to their plan and that is accounting for the plateau — but I’m not talking about that today.

Today I’m talking about weight loss plateaus that are a product of metabolic adaptation. More accurately, adaptive thermogenesis.

When you lose body mass, you will typically expend less energy. If you move the exact same amount, but weigh 20 pounds less, you will simply require less mechanical energy to exert said movement.

Making metabolic adaptation obvious from that lens. But when I’m talking about adaptive thermogenesis, I’m referring to the body’s response to being underfed by conserving energy to defend against further weight loss.

This is most commonly done via the energy expenditure outlet that we know as NEAT.

NEAT stands for non-exercise activity thermogenesis.

Which basically just means all of the energy you expend from movement that is not intentional exercise.

This could be walking, fidgeting, pacing, talking etc.

A great way for your body to conserve energy is to reduce these more subconscious forms of energy expenditure.

With that being said, in the paper I’m covering today we’ll see the body can also reduce resting metabolic rate too.

So adaptive thermogenesis could be defined as an energy expenditure reduction that exceeds the drop that we would expect from body mass loss alone.

This brings me to the paper I want to cover today.

Study Reviewed: Adaptive reduction in thermogenesis and resistance to lose fat in obese men

This study put 11 obese men (according to BMI) through a weight loss program that was broken down into phases.

Each phase consisted of 5kg of weight loss until a plateau occured.

At each phase all measurements were retaken.

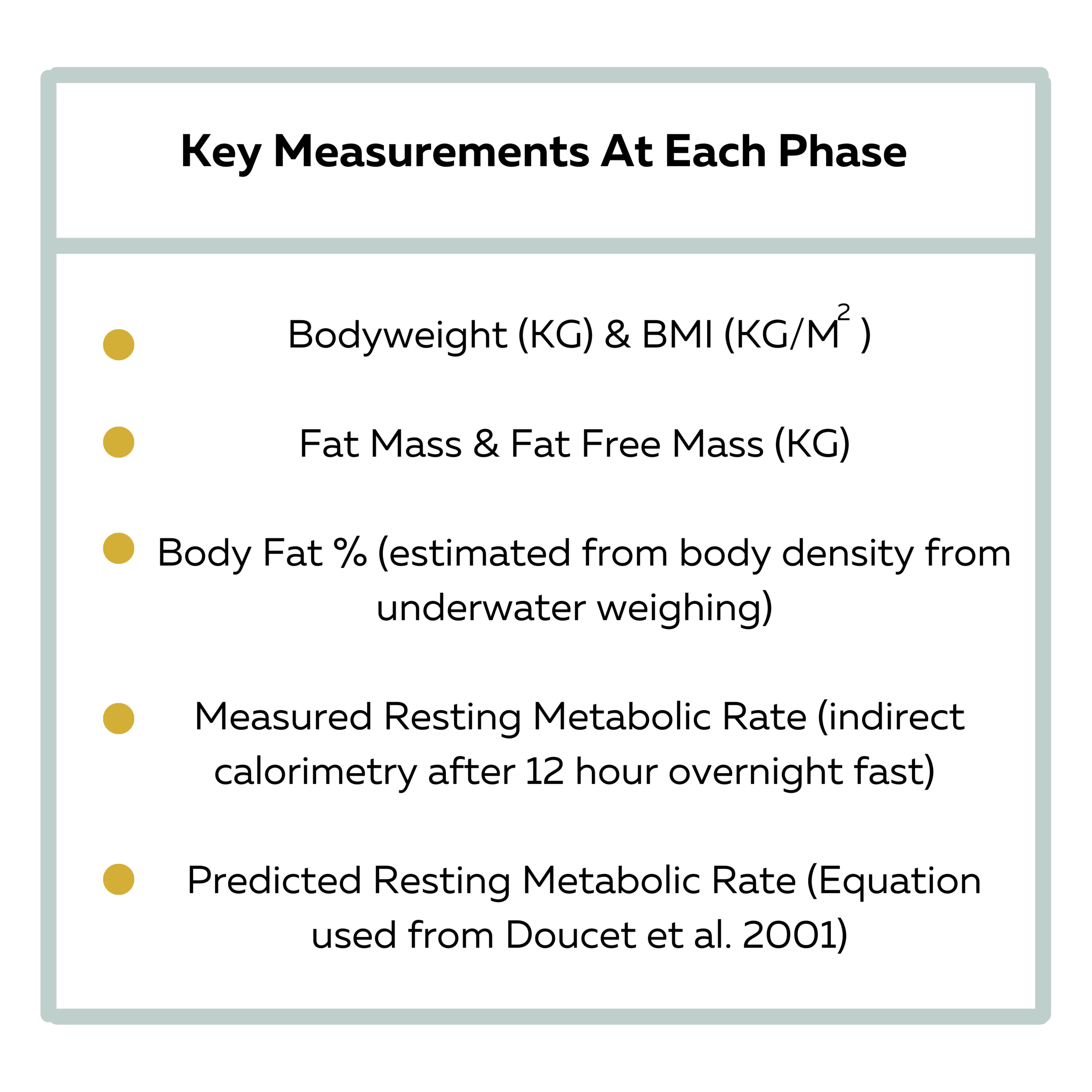

Below is a list of these key measurements:

A dietician put all subjects on a supervised diet that would be approximately be a 700 calorie deficit per day.

All subjects underwent a supervised exercise regimen as well. This consisted of a progressive treadmill workout at 60–75% of VO2 max for 20–30 minute sessions at a frequency of 2–3 times per week.

The exercise routine would progress over time in intensity, duration and frequency. Eventually getting up to 3–5 sessions per week for a duration of 40–60 minutes over several months in the study.

Results

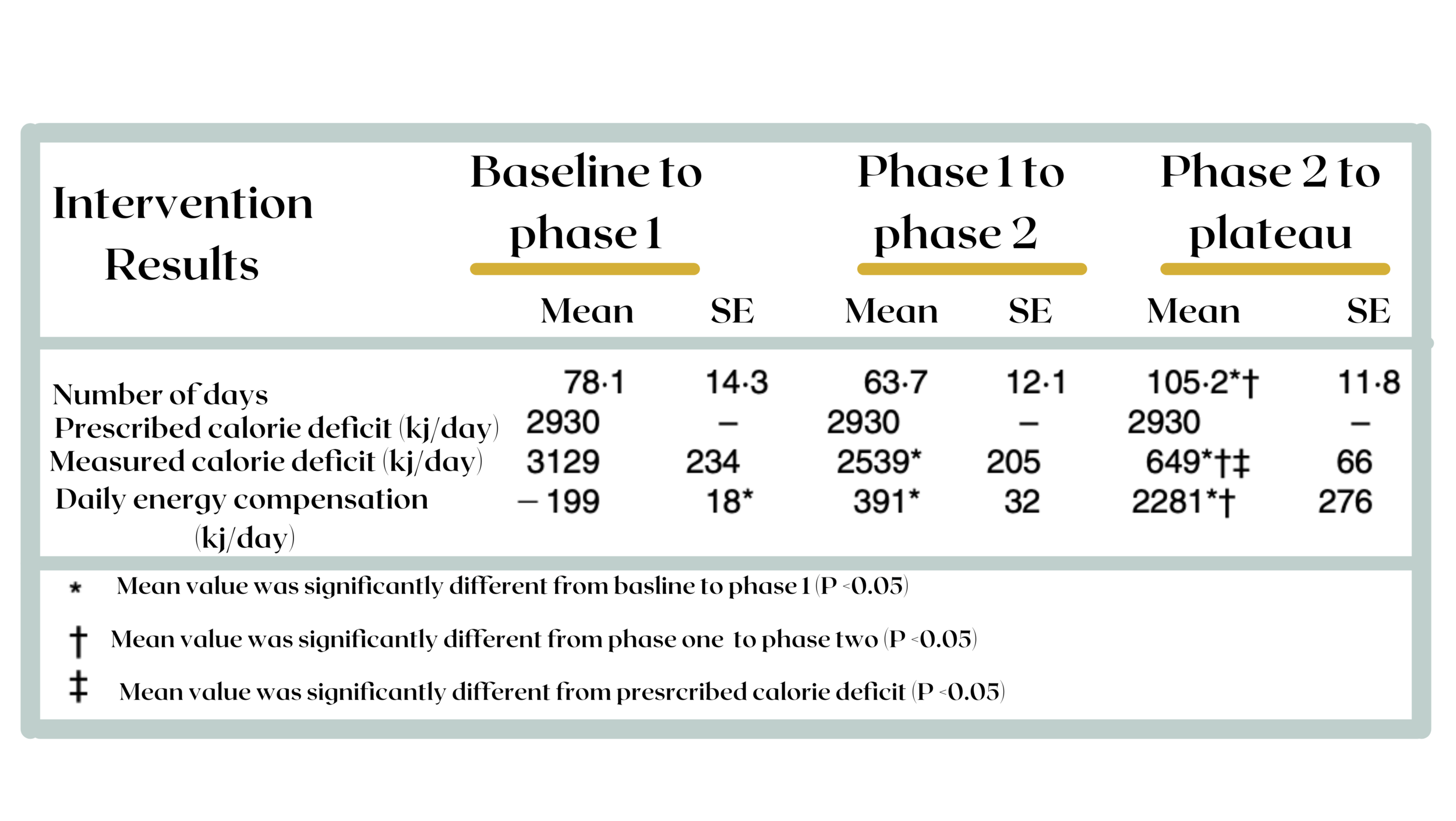

The group achieved two phases of 5kg lost until a plateau was reached after phase 2. Another 2.1kg was lost on average until a complete plateau happened, even though all participants were on what would be expected to be a 700 calorie deficit per day.

If you look above you’ll see that significant adaptive thermogenesis was observed at phase one and during the plateau. But not during phase 2.

This was measured in kilojoules, so I’ll break this down into calories for a more practical understanding of the data.

After phase one of losing 5kg, the measured RMR (resting metabolic rate) was about 100 calories lower than the predicted RMR — which was statistically significant.

After phase two of losing another 5kg, the measured RMR was about 30 calories less than predicted RMR — which was not statistically significant, or even that meaningful.

At the weight loss plateau, the measured RMR was about 168 calories less than predicted RMR. This was also statistically significant.

At baseline, the average measured RMR was 1864 calories per day.

At the plateau phase, the average measured RMR was 1599 calories per day.

This made a 264 calorie drop in measured RMR from baseline to plateau.

For context, the predicted RMR based on only body mass change alone at the plateau phase was 1826.

So instead of the 38 calorie difference that was predicted, an extra 226 calorie decrease was measured at at the plateau phase for resting metabolic rate.

One thing to add on here is that this was only measuring energy expenditure changes through resting metabolic rate (RMR). Which will take up about 60% of TDEE.

In case you have no idea what this means, this is a measurement that is taken in a fasted state (usually first thing in the morning) by measuring the heat you’re expelling at rest. This is done by you laying down and wearing a mask that is hooked up to a machine that measures the gas exchanges through your breathing which can accurately assess your resting energy expenditure.

As I mentioned before, energy expenditure drops also happen by reductions in NEAT, which this method would not cover. Since NEAT is more of an active component of energy expenditure.

So it’s safe to assume adaptive thermogenesis was actually larger than measured by RMR alone. Which was confirmed by the table below.

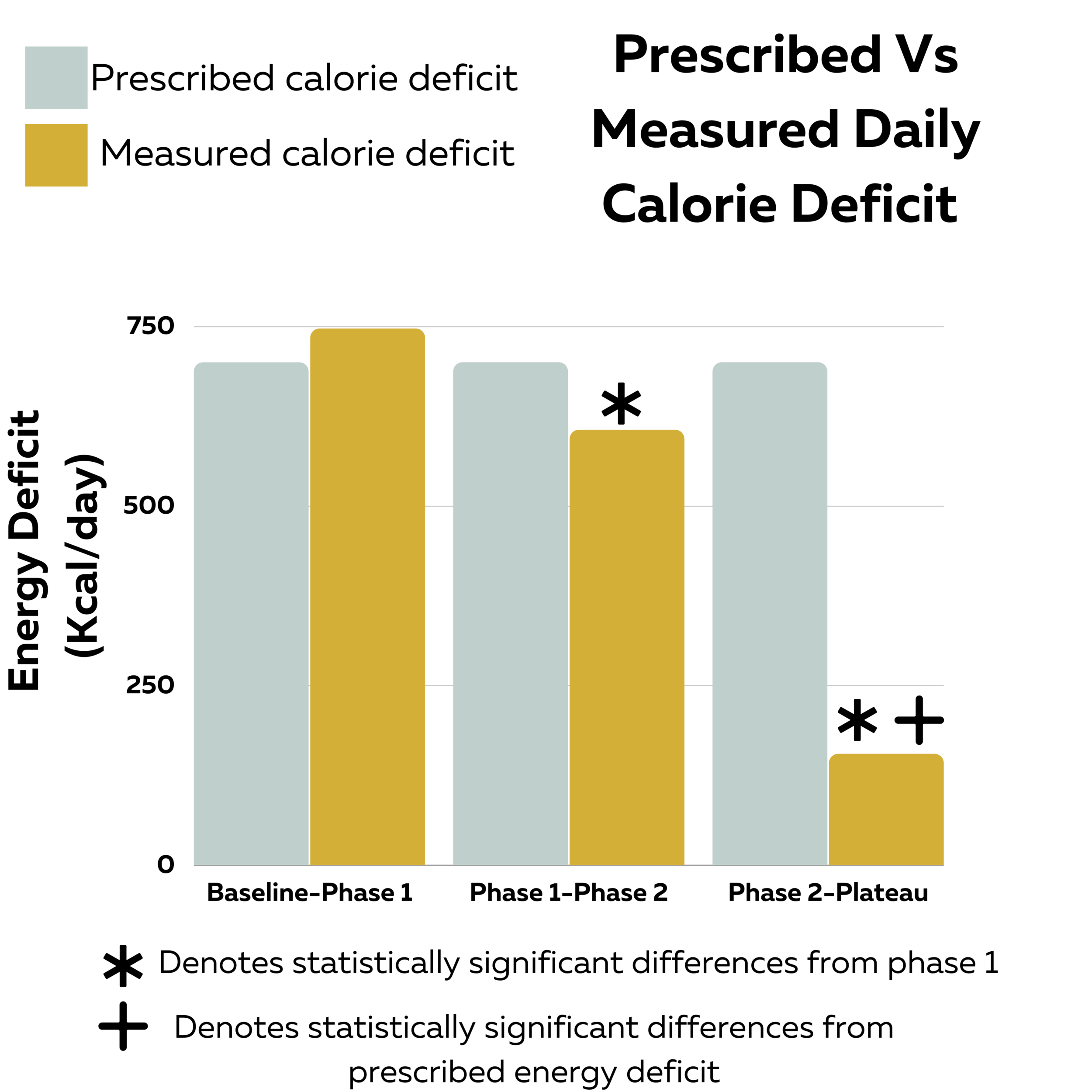

Below you can see how much energy compensation was observed at each phase.

For this article, energy compensation reflects the difference between the prescribed calorie deficit per day compared to the measured calorie deficit per day.

You can see that from baseline to phase one, they were pretty close. In fact, there was more body energy lost than would have been predicted. This resulted in only about 47 extra calories per day, so it wasn’t anything meaningful.

From phase 1 to phase 2 there was about a 94 calorie difference per day favouring the prescribed deficit. This drop was meaningful from the baseline to phase one measurement in regards to measured energy deficit, but it wasn’t a meaningful difference between prescribed and measured energy deficits.

Now, from phase 2 to plateau was where we saw drastic changes. Which shouldn't be surprising considering this was where weight loss plateaued.

While still being prescribed what would be expected to be a 700 calorie deficit per day diet, the measured daily calorie deficit per day for the average of 105 days was only 155 calories.

The average was a 155 calorie deficit per day based on the time period, but it started larger and then obviously became a 0 calorie deficit per day since weight loss fully plateaued.

It’s key to note the the prescribed 700 calorie deficit per day was adjusted at each phase as to move with changes from body mass lost. Meaning the total calories they were on did go down with each phase.

This was a 78% drop in measured energy deficit compared to prescribed.

Lending itself to evidence of real and meaningful adaptive thermogenesis.

At the point of complete weight loss plateau, the average weight lost was 12.4% of initial bodyweight between participants. Based on the measurements they took, approximately 93% of which was from fat stores compared to lean body mass.

To circle back to how individual this response is, 3 of the 11 participants actually hit a plateau at phase 2 and had no further weight loss past that point.

So the data above is from the 8 participants who had gone through all 4 time points.

I bring this up because some people will hit this plateau earlier and some will later.

Lastly, this all took about 8 months to achieve. So before you start feeling grim about your potential weight loss endeavours, just remember a significant amount of weight and time passed before this severe metabolic adaptation took place.

Takeaways

As always, I’ll start this by saying this was just one study on a small sample (n=8) of obese men according to BMI.

With that being said, it was a well controlled study over a long period of time.

Making it a useful study to learn from in the context of understanding metabolic adaptation to a better degree.

The first takeaway here is that after significant weight loss, the maintenance calories of said weight loss may be lower than you’d like it to be.

Using this study as a reference demonstrated this effectively. As what would be expected to be a 700 calorie deficit per day turned out to actually be maintenance for the participants at the plateau phase.

This could be a slap in the face if you expect to lose significant amounts of weight without having to drop your calories even more as times passes and pounds drop.

It’s also key to note this as you may realize your goal may not be as realistic if it means you’ll have to be on unmanageably low calories in order to maintain that result.

This doesn’t mean you can’t lose weight. It means you need to assess and reassess what you’re willing to do in order to actually maintain your weight loss. There is of course, a point where the juice just won’t be worth the squeeze.

The second takeaway I think here is that we need to realize that our bodies will defend weight loss at a certain point.

That point will probably be quite individual too.

Some folks have quite rapid drops in energy expenditure when being underfed. This has been called the thrifty phenotype.

For people like this, metabolic adaptation may be a bigger pain in the ass than it is for their peers when it comes to weight loss.

While this does suck, it is important to know.

As doing everything you can to manage this will be important.

This means making sure to keep activity levels as high as possible during your diet.

If you happen to be someone who adapts rather quickly (with lower than expected energy expenditure) in response lower energy intakes, then having a daily step target or weekly activity goal to offset this could be crucial.

This could also make prioritizing protein even more important due to its higher thermic effect (meaning it costs more energy to eat/digest).

Lastly, it could also mean lowering your energy intake more than you would have predicted.

I wouldn't recommend this if you haven’t already gotten activity up, but if you have and it’s still not budging, then lower calorie intakes than predicted might unfortunately be the solution.

Regardless, metabolic adaptation and more specifically, adaptive thermogenesis is a real thing.

It’s important to understand and consider this when we embark on our weight loss journeys.

How much you’re able to eat before weight loss will simply not be how much you’ll have to eat to maintain that weight loss.

Weight loss is not an easy thing to achieve and maintain.

With that in mind, it’s still possible.

Being informed with knowledge and strategies to combat the obstacles of it is important though.

And this just shows that metabolic adaptation is just one of the obstacles to keep in mind when it comes to successful weight loss and weight loss maintenance.

Here are some additional resources that can help you with your weight loss/weight management goals:

If you’re interested in working with us, we are accepting online coaching clients as well. To learn more and schedule your complimentary consultation, click the box below to apply!

Cheers,

Coach Dylan 🍻

References:

Adaptive reduction in thermogenesis and resistance to lose fat in obese men

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19660148/Biology’s response to dieting: the impetus for weight regain

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3174765/

3. Reduced adaptive thermogenesis during acute protein-imbalanced overfeeding is a metabolic hallmark of the human thrifty phenotype

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34225360/